For The Love Of Science And Journalism: A Journey To Demystify A Rare Disease With Bijal Trivedi

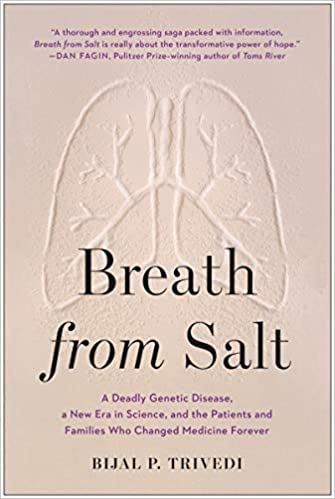

Cystic fibrosis is a rare, inherited lung disease that has been affecting children and devastating many families for so long. Without treatment, it can be fatal. Spreading awareness about this disease and the healing discovery within, Bijal Trivedi, an award-winning freelance journalist, joins Tony Martignetti to share with us the knowledge and wisdom from her book, Breath from Salt: A Deadly Genetic Disease, a New Era in Science, and the Patients and Families Who Changed Medicine Forever. Here, she takes us deeper into the story of cystic fibrosis—from how it gets passed down and what it does to our health to how it could unlock the key to healing millions of genetic diseases of every type. Bijal also shares about her career journey, letting us in on her passion for science journalism and working on demystifying the field to bring more people to understand science better and start the conversation on rare diseases.

---

Listen to the podcast here:

For The Love Of Science And Journalism: A Journey To Demystify A Rare Disease With Bijal Trivedi

It is my honor to introduce you to my guest, Bijal Trivedi. Bijal is an award-winning freelance journalist specializing in long-form narrative features that are about biology, medicine and health. She works as a Science and Technology Editor for The Conversation. She has completed her first book, Breath from Salt: A Deadly Genetic Disease, a New Era in Science, and the Patients and Families Who Changed Medicine Forever, which tells a story of cystic fibrosis, which is a disease that has been devastating for many families. Her book was listed as a top-five recommendation from Bill Gates, and that's an honor. What Bill said about the book was, "I couldn't put the book down. Trivedi leads you on tour through the ups and downs of the discovery process. She gives it life-and-death urgency and emotion. Breath from Salt is an inspiring book. That's my kind of book.” She lives in Washington DC with her husband, two teens and a new puppy named R2.

---

I want to welcome you to the show.

Thank you so much, Tony. I'm excited to be here.

I'm looking forward to digging in and knowing all the insights that have come from your journey to getting you here. I'm especially interested to know a lot about the book itself. This is a disease area that is devastating for many families. I know that you learned a lot about yourself and these families in the process of writing this book.

It's classified as a rare, inherited lung disease. Without treatment, it is fatal. It's a horrible disease. It tended to affect children for many years before there were reasonable treatments for it. You get this disease by getting one bad gene from your mother and one from your father. When they come together, those two mutations disrupt this protein in the cell that regulates salt. It sounds like a minor thing but it completely ruins your lungs. It affects the salt transport in your lungs, makes mucus buildup, and affects all parts of your body. Unfortunately, people usually die of horrible lung infections because the bacteria level and sticky mucus in the lungs multiply and destroy the lungs. It's an awful disease.

I spent a lot of time working at a company called Vertex Pharmaceuticals. I'm a little more in the know of the disease. For me, I understand it. The way you described it brought this more into focus for the people who are reading who may not know that. I deeply appreciate that insight. As we go further into this episode and you talk more about your story, we're going to start by sharing your flashpoints. These are points in your story that have revealed your gifts into the world. As we do that, we'll stop along the way and see what's showing up. As we get further along, we'll see what comes out of the book, the insights that you can share. Where did this interest in Science come from?

If you're going to go back to an interest in Science, then we're going to go way back. Way back is when I was in elementary school. I grew up in Canberra, Australia, which is the capital. It's pretty close to Tidbinbilla Tracking Station, which is one of the huge radio telescopes that the US relies on to keep up communications with the shuttle and a lot of spacecraft. While I was in elementary school, the Voyager spacecraft was going past Jupiter and Saturn. I found the coverage of that riveting. The pictures of Saturn's rings, which I always thought were these solid, flat things that almost looked like you could ice skate on.

Science is incredibly exciting. There's nothing more interesting than it.

When I saw that they were made of floating bands of rocks and there were gaps between them, I was hooked with those pictures. Of course, as a young Indian girl, I learned about Marie Curie and the story of radium. Very early on, I latched onto Science, first, Astronomy. As I got older and experienced different classes in high school, Biology began to captivate me. I pretty much stuck to Biology. Physics, as soon as I couldn't see anything that the Physics teacher was talking about, I couldn't grasp it. I like Visible Sciences, and that does include Chemistry. That's where it all began when I was nine years old.

I love that insight. It's something about things that are not what they seem. When you start to get in and you put your hands on it or at least you get deeper into it, you start seeing like, "There's more to this." I want to know more when your curiosity was piqued.

Even these were black and white pictures in the newspaper. I became friends with an astronomer who worked at the radio telescope. I told him that I wanted to do talks for my class. I remember he showed up at my house. He didn't know my age because I just called him on the telephone. My parents answered the door. He came to the front door with a carousel of slides for a slide projector. He was like, "This is for Bijal." I came to the door and he saw somebody who was about half his height. He was very nice and very kind. He lent me all these slides and all these resources so I could talk to my 6th-grade friends and give talks at school about Astronomy, Voyager and Saturn. It grew from there.

You went from there in 6th-grade, let's call you a Science nerd. It’s continuing your curiosity and exploration, and then you got into college. What did you do in college?

I went to Oberlin College, a well-known hippy, Science College. I studied Biochemistry there. That was eye-opening because I'd done some dissections in my Biology class in high school. To get a peek inside a cell like a cell in Molecular Biology which was a class taught by Dr. Dennis Luck who had done some seminal early research on amino acids. It was so exciting. Learning about DNA in-depth, RNA, proteins, how things worked inside the cell, these things called genes, and how the genes worked completely blew my mind. Of course, we know a lot more now.

The early research in those areas was so fascinating. The fact that people were able to manipulate the activity of genes in bacterial cells and mammalian cells, manufacture protein to orchestrate life, and make the cell into a factory to make whatever you wanted. Who is not excited by that? That is power. That is the ability to change lives and help people. As soon as I took that class, and then soon after an Organic Chemistry class taught by Dr. Matlin, that was my world. I never needed to go beyond molecular. I never needed to go to anything bigger than a cell. I had found my universe where I was happy.

I love the idea of being at that level and seeing how much could be done inside of a cell. There's an entire multibillion-dollar industry that's now circled around this. The possibilities are now endless in unlocking the potential of the cell, which is cool.

Not just for medicine but for the environment, energy, and cleaning up nasty pollutants. It all comes down to the cell. The cell is all-powerful.

Tell me what happened next. What was the big moment that happened after that? You've got these interests. Where did you take it?

Tell me what happened next. What was the big moment that happened after that? You've got these interests. Where did you take it?

I come from an academic family and I'm Indian. As people know that early in an Indian's life, you only have three career choices: doctors, lawyers and engineers. It was convenient that I was so hooked on Science naturally, that I never considered anything other than completing college, getting my PhD, and becoming a PI in a lab somewhere. I never thought twice about doing that. After I graduated from college, I came to the Whitehead Institute in Cambridge. We worked in the lab of Eric Lander for a couple of years. This is when the whole gene hunting business was getting underway. I learned how to look for genes when you don't know what the genes do or the protein they make.

I was a technician in his lab. I got exposure to world-class science and the very competitive universe of gene hunting. I did that for a couple of years. I went to UCLA as I had always planned, get my PhD. I was in a PhD program. About halfway through it, I had finished the equivalent of my Master's, Dolly the Sheep was cloned. One of the things I enjoyed in graduate school was giving talks. You're in a journal club, you read a paper, and you present somebody else's work to your colleagues and peers. You get to share the highlights of that research. That was something I loved doing.

When Dolly the Sheep was cloned, I read the whole article in The New York Times about how it was done, how the science was done, and I saw the graphics. I was like, " I want to tell those stories about science and the people behind the science, not just what gets printed in the journal article. I want to know the motivations of the people who are doing this science and making those discoveries. I wanted to know what made them tick." That was exciting and it was also scary because I never considered anything other than a PhD. I hadn't the faintest idea of how one goes from being an almost scientist to a science writer or science journalist.

Luckily, I had a friend who was the youngest editorial writer at The Washington Post. We'd gone to college together. He told me, "You have to switch to journalism. That's what you want to do." He was the one that laid out to me what I wanted to do was Science Journalism. I couldn't package the idea in my own head because I didn't know about it. That was both a terrifying and an electrifying turning point in my life. Cloning of Dolly the Sheep is a flashpoint in my life, which is funny, that was when I changed direction. Instead of finishing a PhD, which would have been another three years, I decided to finish a Master's and applied to Science Journalism programs.

This is something that a lot of people go through. You've invested so much time and effort going down this path, and you feel like, "I've had this moment that revealed something to me. What do I do with it?" You've made this big decision. When you went into Journalism or went into this course, were you feeling like, "What am I thinking?" Was there a lot of doubt in you?

I was completely consumed by doubt. There was almost nothing else to me. I went to the Science, Health & Environmental Reporting Program at NYU. I had probably more science than anybody in that classroom. There were sixteen of us. It was a small program where you get a lot of personal attention from your professors. Everyone in the class had more writing experience than I did. They were better writers. All I had under my belt was Science. That was the one thing I could flaunt in a way, “You may be able to write it down nicely, but I know this stuff.” It was a nice step-up because I didn't worry about the content. My priority was learning how to write in a style that was newsworthy of magazines and get out of the scientific tone that you use when writing a journal article, which is not exactly riveting in most cases. It was a complete mind shift. It was terrifying because my colleagues were quite brilliant and wonderful writers. I was coming from a different world.

I think about when you first opened up and the way you described cystic fibrosis, it was so eloquently done but in a way that was easy for people to understand, like what does salt have to do with CF? Now, it makes sense. Your gift is there. It was honed over a period of time. You didn't just arrive and start doing this. It goes to show you there's an element of, when you have a passion for learning something, you do it. You put your effort in and figure it out.

Kids are put off by science because it's presented to them in a way that's not very palatable.

My sister reminded me of something. She said that whenever anyone asks me anything to do with Science, even before I switched to Journalism, my strategy is always to pull out a piece of paper. I use my hands a lot when I describe how things are happening. I like to diagram things. I like to draw things out. Science is incredibly exciting. In my humble opinion, there's nothing more interesting than Science. I want people to feel that excitement. Even when I was tutoring somebody in high school, which is something I did while I was in graduate school, I wanted them to be able to see it, feel it and imagine it. I was always passionate about it even though I didn't quite know what it was. It only started when somebody told me, "Write the way you speak." I was like, "It can't be that informal." I didn't realize that. It was one of my first journalism jobs. My boss said, "You're writing too formally, just write the way you speak and you'll be fine." I started to do that and she was right.

There's something that you said earlier that I wanted to clue in on. Science, in general, is a very visual thing. When you start to write, it almost sounds like you have to visualize it first before writing it. Is that correct?

That was also why I was so drawn to Biology because you could see things. When you couldn't see them directly, you could label them with either a dye, something with phosphorous or radioactivity. You could make things seen, you could make the invisible visible, and that was an exciting thing. The other reason I was so drawn to it is when I was applying to graduate school, I found out that I was dyslexic. I bombed the GRE language section. I did fine on the Math but it looked like I couldn't read if you had looked at the language section of the GREs. A friend's father said to me, "You've got a problem. You need to go and get tested."

I went to Mass General and I was diagnosed. It made me reflect back and think, "Maybe that's why I've always been drawn to Science and things that you can see." I liked Chemistry because there wasn't as much to read and the same with Biology. At the same time, I loved writing and English, but I am a glacial reader. Fortunately, I can type fast and I can read. That was a glitch. When I reflected back, it was probably one of the things that made me steer towards the more visual Life Sciences.

Thinking about the early days of you starting to write, here you are starting to get into the field of Journalism and starting to write in this challenging area, of course, you probably made it look easy. Were there any moments where you had a critic or someone who came back and said, "This is no good?"

There are tales of saucy editors everywhere. I won't reveal the publication but there was an editor who was quite nasty. He was very interested in manipulating the story and the science in a way that was more sensational. I think because my background is in Science, I am very sensitive about that. Science is sensational in itself. It doesn't need to be twisted and manipulated. You don't need to hype it up, in my opinion. There was an editor who was trying to do that with one of my stories. That pissed me off to be quite blunt. It upset and disturbed me. I'm very strait-laced when it comes to presenting science. I don't want any errors and any hyping, just tell the story. The story is interesting as it is.

That was at a point where I was trying to decide, "Which way do I take my career?" After a certain amount of writing short articles for new sites and writing long features for magazines, and after this experience with this editor, I wanted more control over my own work. That unpleasant experience may have been one of the factors where I started yearning to write a book where I would have complete control and be able to chart out a story the way I wanted to do it, not to fit with the mold of a magazine or a template that someone else had created. That was the silver lining to that unpleasant altercation.

It's freeing at this point where you can start to see that you're grateful for the experience that brought you into this. You evolved at this point and said like, "I need some space to explore what I'm capable of too." As we enter this time in the talk when we're going to be getting into the book, seeing that you're capable of creating a beautiful book you have and realizing it's something that was in you all the time, it's interesting to see that it all came from the short articles being put under the gun by editors and what have you. What an interesting journey you've been on when you think about it, a small, little curiosity in Science and evolved into this, which is fascinating.

Kids who put off Science, maybe it's presented to them in a way that's not very palatable. Although with the web and Khan Academy, things are very different now. I get so sad when I hear about kids not liking Science. It makes me want to grab them and be like, "Tell me what you don't like, and I'll tell you what it is about." I feel that with adults too. When people tell me, "We don't understand how these vaccines came about. Do you trust them?" That's one of the reasons I'm at The Conversation. I get to work with academics in universities and help them to translate their ideas for a lay audience. It's helping people to tell stories. Everybody would be fascinated and everyone would have greater trust in the scientific process if they understood a little bit better. That's always been a mission, even though maybe I wasn't able to articulate it a while ago. That's what it comes down to.

When you think about it, it's demystifying something mysterious to many people. Even when you don't know all of the ins and outs and how things happen, being able to know how the story and where the holes are. I'm sure there are areas that are like, "This happens but we don't know why." We're being honest, that's the way it is.

“Here's the black box. We don't completely get it but we're working on it. We know what happens on one side and this side. We'll eventually figure it out.”

Not to geek out too much, but looking at how far we've come with some of the disease areas that we are now. We talked briefly about CF. We've talked about CF in the sense that it used to be a children's disease. Now, there are adults who are making it to older age with CF.

The current age is 47, which is amazing. When you think about in the mid-'70s, children weren't expected to reach double digits. Now, it’s 47. With the new drugs that have been developed by Vertex Pharmaceuticals, kids who receive this therapy early enough in their life are expected to live full lives and die of something like heart attacks, cancer or something very mundane, and not cystic fibrosis. That's amazing that they will now be able to have full lives, families, take advantage of their potential, and what could be better.

Just like everyone else has a chance to live a life, these people have a chance to live a full life. What brought about the idea of working on this particular book? What was the inspiration for you to work on this?

My editor at Discover Magazine is Pam Weintraub. She is a God's gift to writers. She helps so much. She steers you and gives you great advice. I adore her. She gave me this assignment. She said, "There's this new drug called Kalydeco. It seems to be a breakthrough drug. Why don't you write the backstory on it for Discover Magazine?" I hadn't thought about cystic fibrosis since I'd been in college, which is when they found the gene for this disease. I was like, "I remembered it was rare and genetic. It’s great, they've found a drug that treats it."

I found out that this drug only treats 4% of patients with cystic fibrosis. I knew this was a rare disease. I was like, "Who gets into this business to make a drug for 4% of a population?" It means that it's only a couple of thousand people. Drug development is expensive, easily $1 billion to $2.5 billion. There's a broad range in there. It seemed there were all these inconsistencies. I didn't understand why the pharmaceutical company would do it. I didn't understand who would fund such a venture. It's for such a small disease. There's AIDS, cancer and malaria. There are big diseases affecting tens of millions of people. Why focus on this one?

Writing is hard. Being a scientist is hard. You just need to be able to propel yourself through it.

As I dug and I started to meet members of the CF Foundation, the CF community, parents and scientists, my brain was exploding as I started to get a grip on the size of the story and understand how these treatments were developed, who funded them, how they came about, how the science evolved, and how the efforts with CF were leading the field of medicine. It's a crazy idea if you think of this little old, rare genetic disease that's been plaguing humanity for millennia. This is one of the first diseases where they tested gene therapy, discovered the actual gene, and figured out what the protein did. It had all these firsts associated with it. I thought, "Why is this disease leading the field of medicine? It’s bizarre."

I wrote a story for Discover Magazine. It was ten pages long, which is very long for a magazine story. My editor said to me, "If you want to write more, why don't you write a book?" She said it offhandedly, and that's where it starts. It was like this amazing epiphany where all my background in Genetics and Molecular Biology was converging with meeting all these amazing people, these parents and these patients. For once, I could see this perfect balance of Science, personal stories and business stories. It all started to agglomerate in my brain. Several people will tell you if you ask, I wrote a couple of crazy letters to some of the people in my book who eventually ended up as the main characters in my book. I said, "I've had this epiphany. This is a story that I have to tell. I have to tell it now. I've never written a book. You've never even heard of me, but trust me, I will tell the story." People said yes to me, which was shocking.

It comes down to your ability to be a great storyteller. It's not just in science, it's the ability to connect with people. That's where part of the gift comes from. It's a beautiful thing to be able to see that your passion for science transcended science. It went right into the fact that these are people who you wanted to see their stories come to life.

I had never seen scientists so committed to the disease and the patient community. Before this, I had been reporting for about fourteen years as a science journalist. When the scientists were explaining this science to me, some of them were in tears because they had watched families lose members of their family to this disease. They had known those children. They had seen the loss and the impact of this loss on the families. They were so moved and committed. Parents who had lost children and had nothing to gain from still keeping their commitment to this disease were fully invested. They were invested in seeing a treatment found.

The humanity in the story, the grit of people, their values, and their willingness to go out on a limit which was the best of humanity all wrapped up in the story. I'd never seen anything like it. I'd never felt so inspired. These were people who had endured a horrible loss. I've been very lucky I've never had to experience anything like that. They never took a day off from this disease or this commitment. I was moved by that. It made me realize how much they were putting into their lives and how much they were extending themselves beyond what most of us would think would be comfortable. I was completely inspired.

I can feel it. It's very palpable. Having been in the space myself and worked in the biotech space reminds me of the passion that people in this space feel coming to work in this area. A lot of the people who become CEOs and founders of small startups are doing it. Their kids are suffering from rare diseases, have been afflicted, or have some family members. There's usually something in their heart that is driving them into this. This has changed you in a big way. This has changed the way that you approach your writing and what you will do next. I'm making that assumption but I think I'm right.

It has changed me watching the drive of people. It wasn't just at CF Foundation, but it was the parents. In particular, Joe and Kathy O'Donnell, who lose their son to this disease, continued their commitment, and became very committed. Joe O'Donnell raised more than $250 million to help fund the initial research that led to these treatments. He's going to laugh if he reads this. He always tells me he's no spring chicken. He's in his 70s. He could be on a golf course every day of the week but instead, he's committed to fundraising. The man can't sit still. He's always achieving and trying to make someone else's life better.

Being around that and seeing that inspired me. I'll always be covering CF until I keel over. It makes me want to tell important stories because they're inspiring and they help people. Especially now when people have endured so much loss, we need these inspirational stories. Also, a part of this book is a memoir and part is a manual. It's inspirational for people who are suffering from rare diseases. The scary thing is 1 in 10 Americans suffers from a rare disease. If you think about that, that's 30 million people. There's a lot to learn from the journey that these people took to develop treatments for CF. It's very instructive to other families and foundations to see what can be done with the right arrangement of resources.

One of the thoughts on this is reading this book and knowing these stories helps them to realize that they're not alone. Some of the people going on this journey of the rare disease don't know who to talk to or they're like, "Am I going on this journey alone? This is too hard for me." To know that there are other people who have gone down this journey and they can talk to somebody, that's a good starting point. If your book is a dialogue that gets started, then we've done our job.

Nothing would make me happier to know that people enjoyed the inspiration they got from the book and helped them chart their own course, either with a disease, with a foundation or developing drugs. If it moves one person and helps change the course of their life, I would regard it as a success. I would be very happy.

This has been so powerful. What is one big takeaway that you have from your journey that you'd like to share with people? As we've looked back at the conversation, what is one thing that you haven't said that you'd like to share?

Don't be afraid to shed your previous careers. It was hard to walk away from my PhD program because I didn't know the way forward. My father is a professor. My mother is a librarian. I found it very difficult emotionally to walk away from that, especially because no one in my family or extended family was a journalist. I had no clue. It's a bit about, "Don't be afraid to walk away from something if you have a strong gut feeling that you're meant to do something else." It's scary, but I acted on my gut instinct that I would be a better storyteller than I would be as a scientist in a lab. I wanted to be that storyteller and I could do it.

I should have been a bit less nervous, I'm a cautious person. Through talking to people, you can always find teachers, instructors and guides. I had no idea how to start writing a book. As cheesy as it sounds, I got a book on how to find an agent, how to write a book proposal and how to get an editor. I want to do everything very step-wise and methodically. It was scary. Now, I looked back on it and thought, "I was overly cautious. I should have dived in." I would encourage people to follow their strong gut instinct. It might be the passion to drive you through something that's a very difficult goal or difficult purpose.

I keep on thinking of Robert Frost. It was like, "You come to a fork in the road, you chose the one that was less traveled, and it made all the difference." You truly did. Think about it, if you were to have gone the other path, would you have felt as fulfilled as you are right now? Probably not.

I don't know. The life of a PI in a lab is tough. It's a hard existence. It was at a time where it was looked down upon if you were interested in going into the industry. That was something I never considered. I looked back on all the people I met at Vertex and thought, "If one of them had been my professor, I might have been in a biotech company and very fulfilled." That might have been the path for me. At that time, academic scientists looked down on the industry. That has changed now. I would have been fulfilled but all of these roads are difficult. Writing is hard. Being a scientist is hard. It's all hard. You need to be able to propel yourself through it. That gut instinct is your fuel to get you through something.

That gut instinct is your fuel to get through something.

What is one book that has had an impact on you and why?

I'm going to be loosey-goosey with this question and say two books. One is The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. That was written by Rebecca Skloot. The other one was The Emperor of All Maladies, which is written by Siddhartha Mukherjee. The reason for these two books is I read them before I started writing my own book. What I learned from Rebecca's book was the way you could weave personal stories in with the science to tell a rich narrative. There's a limit to the narrative. When you write a book, you can weave together many threads and make it as complex or as simple as you want.

She had very rich characters in her book. You could feel them and see them from reading her words. That showed me the importance of having strong characters to propel the story. The science of CF is hard. The science covered in the book is hard. If you have characters who are propelling you through it, then it's easier to tell and read the story. The Emperor of All Maladies woven so much history and culture. That showed me another way to weave in richness into what is a heavy science story. It let me take little charming tangents along the path of this book like, "What was it like to be a woman scientist in the 1930s in America?"

There are many female heroines in this book. That was something that was a real thrill to include. I could have a little tangent in attitudes towards women in the 1930s if you dared to go and become a physician. I could talk a little bit about the first people who did some gene therapy for immune disorders. I could weave and it was like floating along on a river. I could choose any tributary I wanted for a little bit, come back to the main river and keep going. Those books were very influential in shaping my book. Anyhow, those people and authors are brilliant.

I love those recommendations, they are powerful. I've read The Emperor of All Maladies. I've not read The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks but I do know about it. One of these days, I'll have to pick that up and read it.

You'll be better for it. It's a brilliant book.

This has been magical and inspiring. Thank you so much for coming on the show and sharing all of your insights and story. I can't thank you enough.

I love talking to you. It was like having a conversation with an old friend. Thank you so much.

Thank you. I want to make sure people know where they can find out more about you. Where is the best location? Besides buying your book, where else can they find you?

On my website, BijalTrivedi.com. I made my website, it's very basic. It's how to get in touch with me. I'd love to hear thoughts from anyone who wants to share.

I can't thank you enough for coming to the show. Thank you to our readers. This has truly been an amazing episode that is not to be missed. Thank you so much.

Important Links:

- Breath from Salt: A Deadly Genetic Disease, a New Era in Science, and the Patients and Families Who Changed Medicine Forever

- Vertex Pharmaceuticals

- The Conversation -Bijal Trivedi’s Column

- Pam Weintraub

- Joe and Kathy O'Donnell

- The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

- The Emperor of All Maladies

- BijalTrivedi.com

About Bijal Trivedi

Bijal P. Trivedi is an award-winning freelance journalist specializing in long-form narrative features about biology, medicine, and health. She currently works as a science and technology editor for The Conversation. She has just completed her first book, Breath from Salt: A Deadly Genetic Disease, a New Era in Science, and the Patients and Families Who Changed Medicine Forever.

Bijal P. Trivedi is an award-winning freelance journalist specializing in long-form narrative features about biology, medicine, and health. She currently works as a science and technology editor for The Conversation. She has just completed her first book, Breath from Salt: A Deadly Genetic Disease, a New Era in Science, and the Patients and Families Who Changed Medicine Forever.

Trivedi’s writing has been featured in The Best American Science and Nature Writing 2012, National Geographic, Scientific American, Wired, Science, Nature, The Economist, Discover, and New Scientist. Her work has taken her from the Mexico-Guatemala border where she covered the use of genetically modified mosquitoes for fighting the dengue virus to the behind the scenes at Massachusetts General Hospital where she watched trauma surgeons test hypothermia to save pigs with life-threatening injuries to Moscow’s Star City where she blasted off with space tourism entrepreneurs on the “Vomit Comet” for astronaut training. She also edited the NIH Director’s Blog and, prior to that, helped launch the National Geographic News Service in partnership with the New York Times Syndicate, which she wrote for and edited. Her undergraduate fascination with biochemistry and molecular biology at Oberlin College compelled her to pursue a master’s degree in molecular/ cell/developmental biology at UCLA. Her love of writing drew her to journalism rather than to a lab bench—and to a second master’s degree in science journalism from New York University.

0 comments

Leave a comment

Please log in or register to post a comment