Lessons From A Military Career: Conversations On Life, Grit, And Resilience With Shannon Huffman Polson

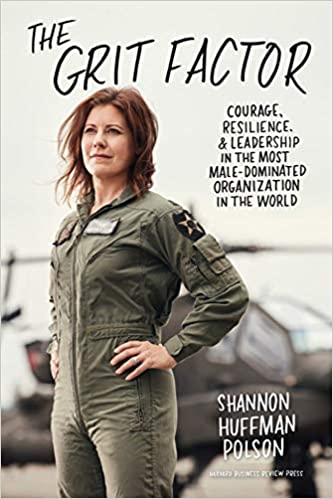

People love to put others in neat little boxes, but life isn't that simple. Tony Martignetti sits down for a conversation with military aviator, leadership development consultant, lecturer, and author Shannon Huffman Polson. One of the first women to qualify for combat duty in the Apache Attack Helicopter, Shannon talks about her military career, the lessons she learned during her service, and how she has worked to transform herself. Shannon and Tony also talk about propelling yourself forward in life, digging into the wisdom from her book The Grit Factor. Join this episode as you learn some key insights on courage, resilience, and leadership that can help you in your journey to transform yourself.

---

Listen to the podcast here:

Lessons From A Military Career: Conversations On Life, Grit, And Resilience With Shannon Huffman Polson

It is my honor to introduce you to my guest, Shannon Huffman Polson. She is the author of The Grit Factor: Courage, Resilience, and Leadership in the Most Male-Dominated Organization in the World. She’s the Founder and CEO of The Grit Institute, focused on whole leader development with an emphasis on grit and creative problem-solving. She served as one of the first women to fly the Apache helicopter in the US Army, before earning her MBA and MFA and leading teams in the corporate world as well. She lives in Washington State with her husband and two young boys, her dog and her cat. I want to welcome, Shannon, to the show.

Thank you, Tony. It is great to be here.

I’m looking forward to creating this ambiance of the fire. It’s a nice effect of having warmth as we have our conversation get started here.

I’m hearing a crackle already. It’s a great start.

I’m so excited to get started to hear your story of what brought you to where you are doing this great work in the world and about your amazing book, which I haven’t cracked the spine yet, but I am looking forward to digging into. I think it’s so great to hear, even just the introduction, there are so much you have done and accomplished. I’m looking forward to hearing your story.

It’s an honor to share and have a chance to talk, for sure.

Just to give you a little sense as to how we roll on the show is we tell your story through what’s called flashpoints and these are points in your story that have ignited your gifts into the world. There may be one or there may be many. What I want to give you is a space to share what you are called to share. We will stop along the way and see what’s showing up. With that, I’m going to hand it over to you and let you take it away.

Some people start in childhood and I will do that because I think it’s relevant. There’s a field called Depth Psychology, where they recommend going back to those things that were important to you before your ego kicked in. That is important to some of the work of The Grit Factor as well. I grew up in Anchorage, Alaska and that is not so unusual if you live where I do now in Washington State but most other places don’t have as much of a connection. My dad had been drafted out of law school for Vietnam and sent to Alaska instead. We ended up staying and so I was an Army brat for about 1.5 years of my life. That was the extent of my military experience, it’s not connected but my dad was very proud of it.

It’s a good reminder not to put ourselves or anyone else into a box and understand that the potential is much broader and deeper than that.

I grew up doing a lot in the mountains, the debate team, swimming and that kind of stuff. As a teenager, I wanted to get as far away from home as possible. This is the end of the '80s. I went to college at Duke University. That would be a first inflection point or flashpoint, probably was the decision to not only go as far away as I possibly could imagine but to go to a whole different environment and a place where I had nobody that had gone before. For some reason, that was important to me. I don’t know exactly why. I know why I wanted to get away from home because I was a teenager but it was the biggest culture shock of my life looking back. Going from Alaska to North Carolina at a point where you had to go through Seattle and take the red-eye to Seattle, and then through Chicago or Detroit and then down to RDU. Now you can fly direct pretty much everywhere, so it was quite the process and the cultural shift.

I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I was a generalist and I ended up as an English major, which I knew I wanted to write. I have always wanted to write. I studied English and Art History. There are no minors at Duke. My major is in English. I was one class short of a double major because I did a study abroad instead. The next inflection point or a flashpoint fairly quickly upon arriving at Duke on the campus was going to college activities fair and ROTC was represented along with everything else, all the Greek systems, the clubs this and that. I knew that finances were tight for our family. Duke was a huge stretch despite having saved and taking out loans and all those sorts of things. I did not consider myself interested in the military but my dad had been really proud of it. I figured I should try this. If I don’t like it, I can at least say that I have tried it.

I was already working at the housing office and working as a waitress. I piled that on top of my other jobs and I ended up enjoying it. Part of it was we had an excellent cadre, which is like the instructors for ROTC. The other kids that were in ROTC were also like me, people, that had grown up working all the time, saving for college, doing all that kind of thing, where there’s a big part of Duke that is not like that. There are BMWs and whatever else. Things that were not in my understanding of things. I related to the kids that were in ROTC. They were great. I also connected to this sense of service and the sense of purpose and serving something bigger than myself. I grew up in a pretty patriotic house, so that was a great way to be a part of a country that I was proud of and make a difference. That flashpoint was pretty significant in the way that my life would end up going.

Even just thinking up to this point, you are showing so much bravery, what’s real grit. Grit is so much more than bravery but I think that there’s an element of like, “Here I am coming out of my element of being in Alaska, coming into a completely foreign place in the first place. Leaping over a place, to ROTC. Are you a tomboyish type of girl all along or is that something that you just feel?

If athletes were tomboys but athletes aren’t always tomboys, I was definitely an athlete and not a shrinking violet. I was captain of the debate team. In that sense, it was very natural to me. I was used to having guys as friends and doing stuff with guys, going out in the mountains and camping. I always think of a tomboy as wearing suspenders and a railroad cap. I wasn’t that kind of a tomboy but I was very comfortable with that kind of life.

Doing it your own way and being your own self in that way, not necessarily falling into, especially during those days, the stereotypes that people would often think of.

I have to give my mom credit for teaching me how to read and all those sorts of things that moms do. I remember when I went to college, she said, “You will probably meet a boy there and you will end up living in North Carolina.” I was like, “Excuse me? That’s not why I’m going to college.” With different generations and perspectives, that was hers and that’s not what I did and I’m glad I didn’t. It was an interesting way to look at it.

After ROTC, you have this experience. You find your tribe if you will. People who you relate to that you can hang and become friends with. What happens next?

After ROTC, you have this experience. You find your tribe if you will. People who you relate to that you can hang and become friends with. What happens next?

One interesting thing is, I don’t feel like I have ever totally had a tribe. I almost pushed back against it because this is an important point because I was also a Student Docent at the museum and I sang in the Duke Chamber Choir and the Duke Choral. At this point in my life, although there are pros and cons, I have never wanted to identify with one group because I feel like it’s very limiting. It also means that you were excluded from some things. There are definitely pros and cons but as a swimmer, there were no other swimmers on the debate team. There were no other debate team members or swimmers at the literary magazine. I never had one thing that I did. I always wanted to be myself and I wanted to do the things that I was interested in that weren’t going to be constrained by what somebody else thought or somebody else did. I bring that up just because that’s relevant probably for going forward.

I was not all-in in ROTC initially. I was not scholarship for the first two years. I just figured I’m going to try it out. I’m going to do a two-year Guaranteed Reserve Forces Duty Scholarship. That means I go into the reserves and I applied for that, which meant that I was also in the National Guard for my last two years of college and serving with an aviation unit while I went to college. That was probably something that lit the fire around aviation. There’s a whole story of how I ended up going to active duty instead of the guard. The guard said, “We don’t want female pilots to serve in this unit. You are never going to fly the TAC Aircraft.” I said, “I’m going to go to active duty.” I went to active duty right when the combat exclusion clause lifted, which meant that Apache helicopters opened up to women. Suddenly, there were many more opportunities than there had been a year before. I ended up going to flight school in Fort Rucker, Alabama and asking for and earning the opportunity to fly the Apache.

You were first in your family to leave Alaska and here you are just blazing a trail again and coming into this really interesting space. That’s remarkable. Not many people can say that they have flown an Apache. It’s pretty wild.

The Army gives you pretty cool toys to play with, as they say.

Tell me about the scariest moment in your experience. I’m not just saying about inactive duty but also in just your entire experience with working in the Forces.

I talk about fear and failure in my keynotes a lot of times because that’s a big point of interest for all of us because it makes us uncomfortable. I can give you an example in the cockpit and that’s cool and sexy. I will say the scariest things for me were not in the cockpit. The scariest things for me were on the ground. When I arrived at my first unit at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, I was 23 years old. I was just trained in the Apache. I was super excited. I cut my hair super short, which is what I’m glad I don’t have to do anymore. I was the only woman out of 120 male combat pilots at 23 and I was not prepared for that.

I was utterly and completely not prepared for what that would mean. I was assigned to a staff position that wasn’t just a staff position but a back-office staff position which was pretty frustrating. I remember going to the captain that I was working for and saying, “Sir, I wonder when a platoon’s going to open up.” A platoon is when you get to fly, you lead and you do all that stuff. He said, “Lieutenant, the Army doesn’t owe you anything.” I then went to the major that I was looking for a few weeks later after he had told me not to worry because I would be being married by the time I was 25. I’m glad to be married now. I was not there to get married.

Fear and failure are big points of interest for all of us because it makes us uncomfortable.

I said, “Sir, I’m going to keep doing the best job I can at what I have been doing but I think I can do more.” I’ve got one additional duty after another and knocked them all out of the park. Finally, I took that platoon and each one of those points was very scary. I didn’t feel like I had support and knew what I was doing. I had never been told I couldn’t do something before. I knew I was able to do it but it was like the opportunity was blocked. I was in this environment that wasn’t particularly receptive. That doesn’t mean there weren’t some great people. There were some wonderful people. The scariest part was asking for what I wanted and being willing to ask again and ask again. Earn it and ask again. I had never been in that position before and I was a pretty young person that was probably ill-prepared for those challenges.

I had a feeling that this was the direction you were going to head in for some reason. What I love about this story is you were like, “I loved it but because it was scary.” The reality is this is something that people go through every day where you are nervous as it is to speak up and say what you want and to put yourself out on the ledge and then to be denied again and again. It’s hard to go through that. It’s challenging and at the end of the day, all you want is your voice to be heard. The fact that you even speak up is the most important thing you can do because at least you can say, “I did what I could to put my voice in the room.”

There is a big piece of it that is you do have to earn it but I knew that I had done what was necessary to make those requests. I talk to companies now where they were like, “We have brand new college graduates and they think they should be the CEO.” I’m like, “No, but you do have to earn your chops.” I had done that. I have been honored grad at flight school. I was getting exceptional feedback for all of the work. I was like, “Come on.” It feels awkward and it feels scary. As a woman and there are other points of intersectionality. The race would add another layer to that, which I did not experience.

You are fighting two fronts all the time, this one thing where people are kicking you out of the room and at the same time, you’ve got the regular responsibilities, which are significant by themselves. That is why when I started to write The Grit Factor, I interviewed leaders and the vanguards of their fields that happened to be women and they happened to be military because they have this dual challenge. This double crucible as one of the professors at Stanford calls it. It was definitely tricky and those were not isolated incidents. There were multiple incidents like that.

I can only imagine. The thing I’m feeling into is this element of everyone has doubts and every person on this planet has doubts. You lean in and you know that you are already trying to overcome those. That’s what you were saying. It’s the double challenge you are dealing with. It’s this element of the doubt you have already in yourself. When you overcome that and then you are faced with this, it’s like, “What else do we have to overcome to be able to get my point across?”

What you hinted at is this battling of entitlement. Am I feeling entitled? Is there entitlement in the room? People feel like I just deserve that because I went to school and I’ve got all these things and I need to have that title because that’s where I am. You have checked the entitlement at the door and you said, “I know that I deserve this because I have done all the things. I have proven myself by my merits of working hard, getting the things that I have done.” There are a lot of things at play there.

Sometimes when people ask a question like that or we are having a conversation about this, they expect them and it is. There are lots of fun flying stories and there were some scary types in the cockpit but the really scary stuff is in the heart. That’s where the real scary stuff is and facing the challenges in the aircraft. I also had been a skydiver and a scuba diver, climbed big mountains, and done long course triathlons. That kind of fear, it’s not that it’s easy to deal with but it’s way easier than the fear that’s inside. I think that’s an important thing to recognize.

I knew I had a kindred spirit in front of me, someone who likes to do crazy things like that. It’s amazing hearing those stories and I can only imagine, first of all, all of the stuff that you have gone through the service. Tell me about what happened next. Once you have gone through your active duty, what did you decide to do afterward? What was the next play for you?

I tried to get out of the Army while I was in Korea but they wouldn’t let me, so I had to go back to Texas and do one more tour. I remember doing what I had heard called the Benjamin Franklin List, where I was looking at law school, business school, and divinity school. I decided that I wasn’t smart enough to be a lawyer. My grades weren’t good enough anyway because I figured you had to have straight A’s. I don’t know if that’s true or not. Also, there are way too many lawyers in my family and I tend to be argumentative, so I didn’t need something that was going to accentuate that particular aspect of me anyway. The divinity school, I then figured I wasn’t a good enough person, which I also understand is a laughable thing from other friends that have gone to divinity school. I opted for business school.

I applied to the Tuck School at Dartmouth. I sent my application on the last day of the last round of admissions, DHL from Kuwait, which probably helped me get in but that’s fine. In August of 2001, I drove from El Paso, Texas up to New Hampshire and started business school right before the Twin Towers fell. Had I not left at that point, I would have been stopped losing. I would not have been able to leave as an Apache pilot with a military intelligence qualifier. It was interesting timing. I was in business school regretting that I was there, to be honest.

I was doing Excel spreadsheets which I hated and accounting which I stink at. I was like, “I’m good at that thing that people are doing and they need right now. I wished that I was there.” That was a hard transition for me to make. I remember I talked to my dad after business school. I was back in Seattle and said, “I wonder if I should go back in or they are asking people to come and to serve.” He said, “Shannon, you have done your eight years. You let somebody else do theirs.” That was what I needed to hear to move on and say, “That is right. It’s not what I want for my life anymore.”

One of the interesting things that I think about at that point and maybe at this stage of your life you didn’t know this but do you have an idea of what you really wanted or was that just like, “We will see what happens.”

I don’t know that I knew how to listen for that but that’s an interesting question because I went to work for a medical device company. I was in sales, which is where they put everybody at first. I then moved over to Microsoft and I was in finance. That is not my calling. I didn’t like it. I remember talking to my dad again because he was the most important person in my life. He was like, “It’s a good job, Shannon. You could do that anywhere.” It was not real finance anyway. It was like trying to make two different systems tie out at the end of the day. It was brutal.

I had a pretty major inflection point or flashpoint when I was six months into my job at Microsoft and I had a phone call from the police in Kaktovik, Alaska, which is off the Northeast corner in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. It’s a longer story than that but when I called them back, I heard that my dad and my step-mom had been killed by a Grizzly bear while they were camping on a kayaking trip in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

I was six months into my job at Microsoft. I figured I was going to have to quit my job but I have a whole amazing leadership story with my boss there, who just said, “You do whatever you need to do. You can come back next week or you can come back in three months. You have a blank check,” which is phenomenal. I had a lot to do because I had to clear out a house up in Alaska that I had lived in for years and do all the things that you do when a household is gone suddenly and unexpectedly. I stayed at Microsoft for several years after that and I had some great experiences, met some great people and learned a ton that I think contributed a lot. I also started to understand that it was not where I was meant to be. I started to feel embarrassed to tell people that I worked there, which was silly. It’s a great company. It was a great job. I knew it wasn’t authentic to who I was.

The scariest part tends to be asking for what you want and being willing to ask again and again.

I started to do some classes in my Masters of Divinity and then decided I wanted to focus on writing, which by the way, go back to Depth Psychology, I knew that as a child. I have been writing my whole life. It’s not like it was a new thing. I would know I wanted to do it for my whole life, so I went back and did my MFA. I wrote my first book, which was about going back and retracing my dad and step-mom steps up in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. That book is called North of Hope. It’s a memoir and a lot more personal than The Grit Factor but there are lots of grit in it.

At that point, I was saying, “I love this creative part of me. It’s really important to me.” I was singing in semi-professional choral groups again, which was amazing to be able to do. I was writing. I was doing good creative work but I do love business. I love making things happen, execution, leadership, the concept and the parts of it that are not often enough focused on, which is the taking care of people. We focused on that in the military. That’s when I started to do keynotes and work with companies and organizations on leadership, grit and resilience. That was another inflection point or another flashpoint of saying, “This is more where I need to be. This is the way that I meant to contribute to the world.” That was a gift to be pushed in that direction funnily, although I would never have asked for the way that it happened.

There’s something about that that is interesting because it is a flashpoint but it’s also this element of seeing that your passion for so many different areas and not wanting to say that you are going to turn your back on the writing or the creativity in general or the fact that you were in the service. You did serve and you have this business aspect. You can have all that but the key to it is finding a way to bring it all together into the package that is you and not have to say, “I have to exclude this to make it work.” You can bring it all together and you can make something that is uniquely you in that way.

I still find that people want to constantly pigeonhole you like, “You write about the natural world and grief.” I’m like, “No, I just wrote leadership.” You write about leadership and you are all about business and grit. I’m like, “Yeah and I also still do music. I write poetry and I watercolor paint.” It doesn’t have to be limited but so we want to put people in boxes and I feel like it’s a good reminder not to put ourselves or anyone else into a box and to understand that the potential is much broader and deeper than that.

This concept of not putting people in boxes and starting with yourself is something that I have said literally to myself so many times and it’s liberating to even just say, “I don’t want to be labeled as that.” I was a finance person myself in my prior life and I’m like, “It feels weird to call myself a finance person because I have so much more than that.”

The other thing that I feel like and I talked to this young lady who is just starting her podcast, she was a veteran from the Army and we are talking about contribution. My focus or what has been propelling me at this stage in my life is not that it’s less adventure, not that you can’t still have an adventure but it is more about thinking very thoughtfully about contribution. What is my purpose? How can I best contribute? I live in a small town in a rural community that has 30% poverty and 45% reduced and free lunch for kids at school.

In my last 4 years and another 1.5 years still to go, I formed a board and we have raised almost $6 million to build a library and we need this library. I believe in it so passionately, public spaces and the opportunity for education. I was like, “What can I do that is significant in this community?” I have operational skills. I hadn’t raised $6 million before but I know people who can. I can learn these things. I can teach myself. I can go out to people and network for this. I have what it takes to be able to move us in that direction. It has been exhausting and incredibly fulfilling because it’s a chance to say, “What are the skills that I have been given or have had a chance to develop? How do I put that to work so that it can benefit people for a long time?” It’s a pretty cool way to approach this part of life.

That is inspiring right there. It’s cool on so many levels because there’s this element of your contribution, part of your contribution is making an impact on people. Ultimately, there’s this element of thinking how many minds will be shaped by that? In 1 and 2 years’ impact, it’s three years of generations.

That is inspiring right there. It’s cool on so many levels because there’s this element of your contribution, part of your contribution is making an impact on people. Ultimately, there’s this element of thinking how many minds will be shaped by that? In 1 and 2 years’ impact, it’s three years of generations.

It’s quite literally going to be generations. The studies are so interesting. For example, like the Jesuits, not to get off on too much of a tangent but anywhere that Jesuits touched down, they were all about education. In lots of places, they then got kicked out for various reasons in politics, history and religion. If you look at the trajectory of the places where the Jesuits actually put that opportunity for education, the trajectory is totally different than the places where they weren’t. Libraries offer that in a way that is equal access. It’s an opportunity. In a place where we are out in rural, in the sticks, it’s important because some people don’t understand technology. They don’t have access to it. They have never even been 20 miles up the road. That kind of exposure, they call it the urban and rural divide or the opportunity divide and libraries are what cross that divides more than anything else.

I can talk about this for hours. There’s something about this idea of bringing people together too, that is really powerful. I want us to shift gears a little bit and think about what are the concepts in the book that we want to make sure people hear, the key things, the lessons that you have learned that you have put into the book.

I will make it brief but the genesis of The Grit Factor was a young person asking me to mentor her. I went out and did a bunch of interviews of leaders in the vanguards of their fields that happened to be women. They happened to be military but they really formed the basis for how the book is structured. There are three parts of The Grit Factor. It ends up being not this discreet thing but a part of our character, part of the fabric of our being that we all have and we can also build it. That’s one takeaway. We all have it, need it and can build it. It’s also not a sustainable operating model, so that’s a good thing to remind ourselves, especially in these times. The three parts of The Grit Factor, the three-legged stool, is to commit, learn and launch.

The place that I have been focusing on because there are a lot of anxiety right now in the world and not knowing what is going to happen in the midst of the fallout of 2020 in so many different ways. The place that I have been refocusing folks is on the commit phase and the commit phase aligns with owning your past. The learning phase is deep engagement in the present. The launch phase is looking towards the future with that foundation and with that engagement. I get into a lot more detail in The Grit Factor but the commit phase is where I think it’s great to invest in ourselves to spend some time right now, which is going back over our lives, like you and I have just done a little bit and saying, “What are the key inflection points? What did I learn at those inflection points? What are the values that come out of the learning at those inflection points? How does that inform my core purpose?”

I lead into all of this with a story, I go into the research and I then leave you with tactical takeaways and exercises but really investing in yourself to go back and understand what your story says. Not just what does it say but how can you take advantage of the opportunity and the responsibility to shape that raw material of your life into the trajectory that allows you to contribute in the most meaningful way. That is a great question and opportunity for all of us.

I feel like I want to drop the mic right there because that is so meaningful in thinking that way. There is this element of seeing everyone as having everything they need inside of them. It’s about chipping away at it and saying, “What does it all mean? What are all the things that you have pulled together at this point mean? How can you use that to propel yourself forward in a meaningful and in the right way?” When people get stuck, it’s often because of the fact that they don’t know what to do with what they have.

Going beyond the doing to what value does that represent for you and is that one that you want to own or is that one that you want to put away because you are not going to take that forward? These are what I’m going to own going forward. This is how it connects to my core purpose and staying connected to that. If you reconnect to that again and again, you can get through any kind of turbulence. It allows you to be creative in the paths that you take as well because you are connected to those core values and purpose.

I have one last question for you and that is very different than what we have been talking about so far. What’s one book that’s really had an impact on you and why?

I find I am a big reader and I’m a writer. I should be able to answer this question so easily but I can think of 25 books that I want to recommend. When I was married, I gave to my bridesmaids two books each, as one of my gifts to them. One of them was West with the Night by Beryl Markham and one of them was The Road from Coorain by Jill Ker Conway. Both are stories of women, one in Australia who wants to be in the world of academia, where women are not really permitted and one is one of the early women pilots in East Africa but she’s actually British. I bring those up, not because those are the books that are the instruction books, the self-help books. There are a lot of good ones there too, that I would recommend but because the power of story cannot be overstated and how we tell ourselves our own story and how we find strength in other stories. I have found strength in both of those stories of Beryl Markham and Jill Ker Conway. I would bring that up because of the power of the story.

First of all, both books are news to me. I am inclined to want to know more about them because it sounds intriguing. When you are hearing someone going through their story of the actual moment by moment and play by play of becoming who they are, it has something about that that lights me up and makes me excited about that. I can imagine people could see that as very meaningful to them beyond self-help. As I said, self-help books have their place but I can totally see that as being something worth sinking your teeth into.

I could have written the entire The Grit Factor just on the concept of the story. Instead, it is one chapter but I also approach every concept through story because it’s how our brains take in information. That’s all very obvious at this point in all of the study of the brain. It’s fascinating and they are fun to read.

I can’t thank you enough for coming to the show. This has been just amazing, heartfelt and also very eye-opening. Thank you so much for coming on.

I really enjoyed it. Thanks so much.

I also want to make sure that I give people a chance to find out where they can find out more about you. What’s the best place to find you?

I’m online at ShannonPolson.com. I’m often on LinkedIn, Twitter, and Instagram @ABorderLife. I would love to see any of your audience there and The Grit Factor is available anywhere books are sold, so Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Bookshop or your local independent bookstore, which I always like to plug. They can order it for you if they don’t have it on the shelves. I look forward to hearing from your audience what they think of The Grit Factor.

I’m sure they will be running out and getting a copy of the book now because, from everything you have told us so far and everything that I have read about it, I can’t wait to start ripping into it. Thank you so much and thank you to the readers for coming on the journey. This has been amazing.

Important Links:

- The Grit Factor: Courage, Resilience and Leadership in the Most Male-Dominated Organization in the World

- The Grit Institute

- North of Hope

- West with the Night

- The Road from Coorain

- ShannonPolson.com

- LinkedIn - Shannon Huffman Polson

- Twitter - Shannon Huffman Polson, Speaker, Author, Veteran

- @ABorderLife- Instagram

- Barnes & Noble - The Grit Factor: Courage, Resilience and Leadership in the Most Male-Dominated Organization in the World

- Bookshop - The Grit Factor: Courage, Resilience and Leadership in the Most Male-Dominated Organization in the World

About Shannon Polson

Shannon Huffman Polson is the author of The Grit Factor: Courage, Resilience and Leadership in the Most Male Dominated Organization in the World, and the founder of The Grit Institute, a leadership consultancy committed to whole leader development and a focus on grit and resilience.

As one of the first women to fly the Apache helicopter in the U.S. Army, leading line units on three continents, Polson combines her passion and firsthand experience in and study of leadership and grit to deliver world-class keynotes and training to companies and organizations on leadership and grit.

After serving for a decade in the armed services, Polson earned her MBA at the Tuck School at Dartmouth and led outstanding teams in the corporate world at Microsoft. Polson lives with her husband and two boys in Washington State.

Love the show? Subscribe, rate, review, and share! https://www.inspiredpurposecoach.com/virtualcampfire

0 comments

Leave a comment

Please log in or register to post a comment