Question Yourself: Discovering Who You Truly Are With Hal Gregersen

When you question yourself, you discover who you truly are. Tony Martignetti’s guest today is Hal Gregersen, a bestselling author and Senior Lecturer of Innovation at MIT. In this episode, Hal shares with Tony his childhood experience growing up with an abusive father. From that point on until adulthood, a shadow question always haunted him, “how can I make X happy?” It wasn’t until he turned the shadow question he hated for so long into a keystone question for himself that he found his true purpose. What is Hal’s purpose? How do you discover yours? Join in the conversation to find out!\

---

Listen to the podcast here:

Question Yourself: Discovering Who You Truly Are With Hal Gregersen

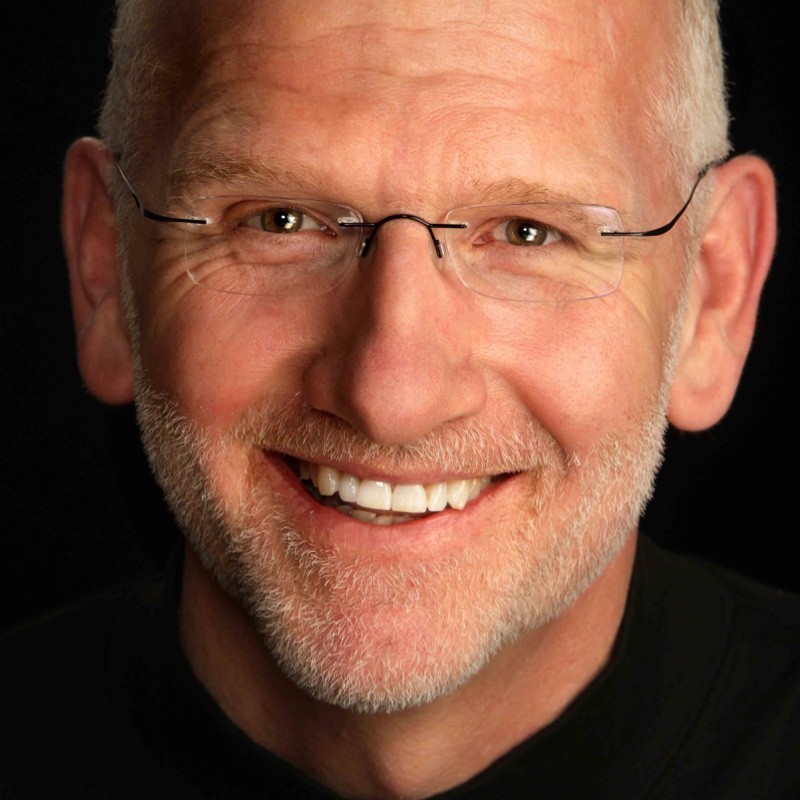

It is my honor to introduce you to my guest in this episode, Hal Gregersen. He's a senior lecturer in leadership and innovation at MIT Sloan School of Management. He’s a former Executive Director of the MIT Leadership Center, a fellow Innosight, and a Cofounder of the Innovators DNA consulting group. As an inspirational speaker, he has worked with such renowned organizations as Chanel, Disney, Patagonia, UNICEF, and the World Economic Forum. He was recognized by Thinkers50 as one of the world's most innovative minds. He has authored or co-authored ten books translated into fifteen different languages, including his bestseller Questions Are the Answer: A Breakthrough Approach to Your Most Vexing Problems at Work and In Life and The Innovator's DNA: Mastering the Five Skills of Disruptive Innovators with Clayton Christensen and Jeffrey Dyer. Hal and his wife, Suzi Lee, lived in England, France and the UAE before landing on Boston's North Shore, where she works as a sculptor, and he pursues his lifelong avocation of photography. I want to welcome you to The Virtual Campfire, Hal.

Tony, thank you. I can hear the wood crackling in the background.

It's an amazing visual and it's a great feeling to be near the fire. One of the things that I love about this theme of the campfire is that it's where stories have been told for centuries. It's a beautiful place to be. I'm looking forward to digging into your story of what made you into the person you are now.

I look forward to digging into that as well because every time any of us dig that direction, we always uncover new nuggets. We're on a gold dig here together.

What I've done is I've created the structure of looking at it through what's called flashpoints. These are points in your story that have ignited your gifts into the world. Some people say that there's one or two that have been big. Have as many as you want or as little as you want. As you're telling your story, let's stop along the way and see what themes are showing up. I'm going to turn it over to you and let you take it away.

Do you call them touchpoints or flashpoints?

Flashpoints. It’s very intentional. It's about fire.

I would say the flashpoints in my life, more often than not, were the moments when I got severely burned. One of those sounds like a strange first starting point, but it's being born into a family. My father was a construction worker. My mother was a stay-at-home mom and sometimes elementary school teacher. I moved seven times before I was five years old. My father would travel the construction sites across the United States. I had an older brother and sister. Two of us had legitimate ADHD. My other sibling has ADD. Imagine a family of five inside of this 30 x 8 feet tin can traveling across the country. We were full of energy. I can't imagine what my parents were like, especially my mother dealing with this.

I had rich and fond memories of that life when I was young, but I quickly learned that in our home, pretty much everything revolved around our father. It would be emotionally abusive, sometimes physical but he was the center of everything. Everything revolved around him. If you didn't please him, sometimes it became dangerous. It felt that way and it was that way at moments. Imagine you're this little kid growing up in that world with this dangerous being around you. You learn fast how to make sure that you do things, say things, even think things that would somehow calm down that dangerous force in your life and keep you safe.

Eat right and exercise. Learn everything there would be to know about not having a heart attack.

All of that leads to me growing up with now, in retrospect, a very legitimate question for a four-year-old. How can I make this person happy so that they don't hurt me in some way, shape or form? When you're young, and you don't have a good understanding of how the world works, that's a legitimate question. It's like, "How can I make this dangerous adult happy?" When you grow up that way and all those memories get laid deep physiologically into your head, then you become this thing we call an adult. Whether you know it or not, I didn't know it when I was younger, I kept living that question. Instead of my father, it was, "How can I make this teacher happy? How can I make X happy? How can I make my boss happy? How can I make my coworkers happy?" That question had its upside, which was an enormous commitment to working hard and to try to please other people by doing things and doing things with impact.

That's the upside of the question, but the downside is that comes to a point at which you're either doing too much or too many at some point. It hits you smack between the eyes. I would say that was my first flashpoint as you call it. It’s growing up in that world and what I call a shadow question of how can I make someone else happy? I've dug deeper into the fantastic work by Bob Kegan around hidden competing commitments. As I unraveled that myself with colleagues and counselors over the years, the underlying question was, will I ever measure up and matter? When I say that out loud, it's still slightly embarrassing to this day but it's life, real and powerful. It still holds its magnetic, attractive and sometimes destructive energy if I'm not aware that that question is operating in contexts that are senseless.

I want to take a moment because that's such a powerful thing to put in the room. It's very true about how there are certain things that don't ever go away. You manage, recognize and see them but ultimately, it's more about how you embrace them and move forward with that. I can relate with this people-pleasing, which is what I'll call it and should we call the same thing, but it's using attitude that shows up in a lot of people who get stuck in that doing mode, which is what it seems like you had. That's what it is. It's people-pleasing. It wants to show up and say, "I want to measure up. I want to do what I can to please these people in my life." That's a powerful beast to slay.

I always find a bio of yourself hilarious because it always feels like an obituary being written of your life. It's being read of your life. I've had the chance to work with some amazing co-authors and colleagues, and do some research on some of the most innovative leaders in the world and worked hard. Working hard commitment originated when I was young. My dad and mother were both excruciatingly hard workers. I'll never forget when I was a teenager, one time saying to my dad point-blank, "Are you a workaholic?" I was that late teenager who’s like, "Please pay attention to me. I'm more important than your work." Legitimately, there was some truth to that, but when I had teenagers, I realized, "I'm doing the same thing my dad did."

That message came home in 2014 when I was living in Boston, working for a French-based university. My work commitments were all over the world. I was traveling intercontinental 2 to 3 times a month for two years at that point. I was getting up in San Diego, getting ready to give a speech. I was feeling pressure on my chest, thinking it was anxiety. I was setting up to talk, then going down to get ready for the talk in the big auditorium and the hotel. I was feeling the pressure still, going outside and saying a little prayer. Getting some fresh air, giving a 90-minute speech, coming back in. I gave the speech and then the pressure comes back with intensity. I get achy. I'm nauseous. I want to get out of there. I go back to my hotel room with the quickest break I could find.

I'm trying to be nice to people, so I don't say anything. My wife's like, "What's going on? You don't look well." I told her what I just told you. She said, "Are you having a heart attack?" I said, "I have no idea, Suzi. Let's check." I pulled my computer out and typed in heart attack symptoms. I checked all these things. I'm like, "Suzi, I'm having a heart attack." She's like, "I just exercised. Can I shower, then we go to the hospital?" I was like, “No, we’re going now.” We went and when I got to the hospital, I was so emotionally overwhelmed. I couldn’t even talk. I woke up the next day with 3 stents in 2 arteries that were 80% to 95% blocked depending on the artery.

I’ll never forget, two weeks later, I’d been a classic male not talking to anybody about the heart attack experience, holding it inside and being tight about it. We are a blended family, so we’d been working with the marriage counselor to shore our marriage up in our family for years. I was talking with her and she looked me right in the eye. She said, “Hal, if you don’t stop being nice to people, you are going to gift yourself a second heart attack.” She was just being point-blank with me. This shadow question of how can I measure up matter? How can I be nice to you? It was killing me.

What I find interesting about this is you’re a brilliant person and yet, here’s the thing. What the most brilliant people in the world often overlook are the things that are just hiding in plain sight.

It was an intentional overlook. I’m four years old. I’m in Southern Utah. My grandparents lived on a farm. My father had something happened that as a four-year-old I didn’t know what it was, but they called it a heart attack. I remember holding my grandmother’s hand as my mother drove my father away. The only thing I can recall is wondering if they’re going to come back. When I was thirteen years old, he had another massive heart attack. In his mid-70s, he had a massive heart attack during an uncle’s funeral when he finally died. It was heart attack, heart attack, heart attack.

I made a commitment at eighteen years old that I would never have a heart attack. I would eat right. I would exercise. I would learn everything there would be to know about not having a heart attack and I did. I’ve been pretty good about it, but that commitment to not having a heart attack created the blindside which was I was overconfident in my ability to not have one that I never took the time to learn what heart attack symptoms were because I wouldn’t have it. I got massively blindsided by what I didn’t know and it almost killed me.

It’s like you turn away from it so much that it blindside. You almost put it out of your mind that it’s even possible. You have this event and now you’ve got this epiphany where you’re saying to yourself, “Now it’s for real, I have to do something about this.” How did you change yourself at that moment when you talked to the doctor and the doctor said, “What are you going to do now?” Did you make the change?

Truth be told, moderately over a long period of time, I still wrestle with the same challenges. I remember being in graduate school. One of my professors said, I think it was Bonner Ritchie, “Hal, people in psychology and social psychology pretty much study what they don’t know, what they’re not good at, their own challenges or the things they’re wrestling with.” One of the research streams that I pay careful attention to is leading change and navigating transitions. I’ve had the chance to interview amazing people who are exceptionally good at it and worked with colleagues who have been helpful in framing a framework around it. When the rubber meets the road and it comes to something like this, it’s still not easy to move away from that shadow question.

It’s a constant presence and being more aware of it. Frankly, I did an okay job for the first six months of being a little more careful because I could live legitimately say to myself and others, "I just had a heart attack. I'm not going to do this, thank you," and then I felt like they understood it. If I look back, that was years ago, it crept back. Old patterns slowly crept back and the fascinating thing is COVID. We have the pure luxury of living on Boston’s North Shore near the ocean. While COVID for us had its isolation effects, it was nothing like being in a small, constrained space in the middle of a city, stuck. I will admit with deep gratitude and privilege that it’s been a privileged COVID experience.

Having said that, it’s been an amazing experience to stop traveling. I’d say at one level. It’s been the best thing ever for me to change some of those habits. It’s also created other problems but on that front like stopping traveling and stepping back. I’ve not yet been on an airplane. My wife just got back from a flight. When she left and came back, getting stuck in the tornado hurricanes of the Southern United States, I’m like, “I’m glad I’m not flying right now.” The point here is, for me, COVID has been a time to rethink what matters, what doesn’t and why. That’s helped me put the shadow in better context, which is, “You don’t matter as much as I thought you did and you’re certainly not relevant to this moment. Thank you, shadow. Why don’t you just take a vacation? Sit back, hold tight. I know you’ll be back but I’m aware you’re there, but you’re not going to push my buttons this moment.”

It’s like that the thank you for your service. You’ve done a great job of keeping me safe. We’ll come back to this one when I need you.

That whole part is its own journey. In 2006, I left London business school and went to teach. We moved from London to the Paris area. I taught at INSEAD. I met Roger Lehman, who was a faculty there. Roger had been trained as a psychotherapist and was the co-director of their Consulting For Change program. It’s world-class and they’re exceptional in what they do. Roger and I became good friends. Professionally we were colleagues, then close friends. For the last 3 or 4 years, Roger and I have been doing research, writing, teaching programs around navigating change and leading transitions and so on. It's been a fascinating journey because, in conversations with Roger years ago, I finally realized I have been trying to completely shut down that shadow question.

You’ve got to be asking a lot of questions to live a life worth living.

I’d been working hard, believing that if I work hard, it will go away. It will no longer be part of my life. It will never be there. It’s Roger’s friendship and professional expertise and a lot of conversations that I find the door and window. The spark finally came, which was like, “It’s not going to go away.” That was the moment in which I started down a path of purpose and what I call a keystone question. To myself, my purpose and why I do what I do is I’m an instrument of inquiry. I’m inspiring others to see the dark, seek the light and embrace the hidden homeless. That last part, I’ve never really done. I had resented that shadow. I had hated that shadow and that shadow was me. I’ve come to realize that shadow is a friend. It’s not a foe. It’s a friend. If I’m aware of it. Let it be my friend in the moments when I do need to be safe. Otherwise, let it sit in the passenger seat and go along for the ride.

There are many things about what you described, which I want to recognize. First of all, this deep inner journey that you’ve taken takes not just you going on the path of committing to understanding yourself better to see what’s underneath the covers. Also, to seek out the help of friends, of people you trust to have those conversations with them as well, to share what’s going on for you, which is super vulnerable. Also, there’s a power behind that. By opening up to them and having them see you fully for who you are, they're able to help you to navigate the world in a different way. One of my taglines is about inspiration through deeper and honest conversations. Sometimes it’s with yourself and sometimes with other people who you need to have those conversations with. I would love to hear your thoughts on that.

You were probably aware that many years ago, I discovered working with a group of leaders who were wrestling within the organization around gender equity. The group of us were in a room. We were stuck. I had this insight that came from a book that’s changed my life. There’s a series by Parker Palmer. One of the initial ones I read was To Know as We Are Known, and then it was Let Your Life Speak, then it’s A Hidden Wholeness and On the Brink of Everything. His fundamental story, all of that is you've got to be asking the right questions in order to live a life worth living. How do you create that sacred space where questions can emerge that will cause us to rethink and reflect, not just react but recharge in a way that can take us in a different reaction?

At that moment with that group, I’m like, “Let’s just stop. Let’s play Parker Palmer here for a minute. Let’s ask nothing but questions.” We did and at the end of ten minutes, where there were no answers, no explanations or questions, the energy level in the room went up, reframing of the issue, ideas to move it forward. I’m like, “What miracle just happened here?” Many years later, I call it the question burst but essentially, it could be one minute alone, just setting a timer and disciplining your head to not ask questions, not answer questions. I’m not answering questions. I’m not explaining why but ask nothing but questions. The data are if we do that individually or to the people, 85% of the time, they will feel better, reframed slightly and at least get one new idea. That’s worth 1 to 4 minutes.

I’m going to come back to your point, which is I was doing a workshop around asking better questions of yourself and others internally within MIT with administrative assistants who work with faculty to help them do their work. Administrative assistants are core to what you’re doing. My struggle has always been, how do I work better with them and give them substantive work? I wrestle with that and I wasn’t not intending to be in a trio doing question burst. Imagine this is you, me and somebody else. Each of us takes a couple of minutes to share our challenge, then we stop. We don’t spend more than two minutes sharing it because we over-explain and everybody else gets stuck like we are. We then set a timer for four minutes and we ask nothing but questions at each other. I explained that and there was a group in the room that was one person short. I’m like, “I’ll do it with them.”

I got in that group, two other administrative assistants sitting in that group or staff in that area, and first-person did their challenge, second, then it became mine. I’m like, “This is my challenge.” I’ll use one related to my administrative assistant in work with her. I shared it. Two minutes is up, question time. One of those administrative assistants looked me right in the eye. The first question of all of them, she said, “Hal, do you have control issues?” I’m funk. She shot the arrow right to the heart and it hurts. It was uncomfortable and it was true. The power of a question burst is you can’t respond. You’ve got to let it sit. There’s that reflective, quiet space. It’s moments like that that makes me realize, “I do have control issues. I do wrestle with that and it’s part of why I’m obsessed with doing things.” That’s what control issues people do.

It’s part of our makeup. You just got to roll with it. It’s the DNA.

Tough questions that aren’t intended to hurt you, they are non-toxic but tough, can be such a gift.

I love the way you framed that. There’s an element when the question is asked from the right people, from people you trust to give you the frank question, and not because it’s coming from a place of malice or they want to hurt you. It’s powerful. It helps you to think, “I am showing up that way. That is something that is real for me.” That awareness is all you need at that moment. The question burst technique is something that I’ve been using in some of my coaching sessions. It’s such a great thing to do but it is sometimes challenging. People sit on their hands for a little bit and say, “I’m not going to answer it.”

I love the way you framed that. There’s an element when the question is asked from the right people, from people you trust to give you the frank question, and not because it’s coming from a place of malice or they want to hurt you. It’s powerful. It helps you to think, “I am showing up that way. That is something that is real for me.” That awareness is all you need at that moment. The question burst technique is something that I’ve been using in some of my coaching sessions. It’s such a great thing to do but it is sometimes challenging. People sit on their hands for a little bit and say, “I’m not going to answer it.”

Whether it’s a group of fifteen people in a room or 10,000 in a stadium, I can always sense at least 10% of the people who are like, “Gregersen, I get what you’re asking me to do, which is to turn on to my neighbor that I don’t know next to me and tell them I have a problem, then let them and me ask all the questions we can about it.” I can see it in their eyes. They're like, “No way am I doing that. I’m afraid. I’m vulnerable. That’s way too dangerous." They have given their ten minutes to do the question burst processed and I can see them talking back and forth. I know they’re not doing it because you’re right.

When you follow those rules in a conversation, if you and I were to do it right now, it's like questions only, no answers, no explanations of the questions. We're going to have a quiet space. We don't like that quiet space sometimes, but it's a crucial quiet space. It's the space between that allows us to see things we've never seen before. Not just see but feel at the heart emotion level. That's the power to me of that question burst process. You can do it alone. I do it like you in a coaching setting. At the right moment, this is what we need here. It will help us unlock, loosen and reframe.

At this moment, I feel like I want to ask about something completely different in your world here because I know you're an avid photographer. I want to know where did that come from. Is that something that you discovered along your journey? Is it something that you had as a hobby that you started to tap into? Tell me about your passion for photography.

I’ve never framed it this way before but I think part of it came from more of my father than my mother because he was an engineering construction sort of mind. He loves mechanical things. He built this van that had at least 100 different sensor mechanisms. They’re all analog sensors. One of which he’d picked up from an old crashed airplane. It’s the wind sensor that tells you how fast the wind is blowing. I forgot what they’re called. He had one of those on his car. He drew this schematic for the vehicle and this is how he thinks. He used that same rigor and logic.

He had a camera. He had an 8-millimeter movie camera too. It meant a lot to him. He’d spend lots of nights splicing and editing the film. I grew up with the smell of that splicing fluid to put the acetate, the films together when they’re cut and spliced. I still remember that smell, that scent and that feel to this day. I always wanted to have a real camera, not a little Instamatic thing. I broke my leg skiing when I was fifteen years old on Christmas day. My parents didn’t have a lot but they found a used 35-millimeter camera and they gave it to me. I ran outside and took my first picture. It survived somehow to this day and I fell in love with taking photographs.

I took photograph after photograph. I’ve worked twenty different odd jobs before I was an adult and saved my money. I ended up buying a medium format camera that professional photographers use. This guy named Elvin Howlett ran Midville Camera. He was the owner and the proprietor manager of it. He's a little guy that’s stock through like me, but short, bald head like me. Little Elvin would be so interested in this gawky, seventeen-year-old teenager coming through his door. He would answer my questions. He’d help with my camera. He’d help with the darkroom. He’d show me what to do. He’d give me tips. I ended up being a wedding and portrait photographer in late high school. I paid my way partly through college by doing that. I loved that moment of learning enough about someone that I could potentially capture the essence of who you are through the lens.

I love photography and then there was this moment. I was in love with it then. I was planning to be a professional photographer. That was my life. Forget this research stuff. All I wanted to do was photography. Last semester of college, which I didn’t want to be and I hated school, but my dad was like, “You need to go to college,” so I did. Last semester, I took a leadership class with a guy named Joe Bentley. It was fascinating. At the same moment, I took the wedding photographs of one of my close friends. I took the photographs with a borrowed professional’s camera because mine was broken and I got the photographs back three days later.

Learn enough about someone that you could potentially capture the essence of who they are through the lens.

This was analog. You had to wait for the photos to come back. They were all white. None of the films had been exposed. My friend had no photographs of his wedding. I had forgotten to pull out what they call a metal dark slide the keeps the light from the lens hitting the film. When you can change film backs on these large cameras, I had forgotten in the anxiety of using the new camera to pull that dark slide out the whole time. I’ll never forget the rotary dial. It still hurts to say this to you, to hold the phone there and to tell him he has no wedding photos. It hurts so bad that over the course of the next five months, I stopped taking photographs. I didn’t know how to deal with that kind of rejection, largely self-rejection.

I didn’t know how to deal with it. At the same time, Joe Bentley was teaching me leadership like, “This is fascinating “ That’s the mother side of me. She grew up in this city called Park City, Utah on the West. Utah has its cultural enclave of uniqueness but Park City is a mining town that was a cross-cultural polyglot of people from all over planet Earth working the mines in Park City. My mother was always curious about people and loved people. That was her gift. I stopped photography, went down this leadership path, got my PhD and did all this research.

After my first wife passed away, unfortunately and tragically, I then remarried. She’s like, "You used to take photographs. Why don’t you anymore?" She talked me into buying a camera. The camera came to my house. I waited a month to open the box because the pain was still there from that prior experience. I fell in love with it again once I started using the camera. My wife was a sculptor and was taking a workshop in Santa Fe. I was bored. I went to Santa Fe Workshops. I met Reid Callanan, Director and Founder of Santa Fe Workshops. I just wanted to take a workshop. After a three-hour conversation, Reid's like, "Hal, you should be teaching a workshop with somebody else."

He introduced me to Sam Abell, a National Geographic Photographer for 30 years. His work is amazing. Look at his website. Sam is a spectacular photographer, a brilliant observer of the human condition, and a marvelous teacher with clarity of photography in life. I started working with Sam. We did workshops together, taught workshops together. Now I can’t think about any research topic without thinking of how photography might change the way I look at that, inform it differently, and give me more insight into the issue. It’s come full swing back to the deep integration of a childhood love with now a professional arc.

The story is powerful on so many fronts but in the closure of that, it came full circle. You’re able to bring that passion of where this art of photography and your business of being able to see people deeply, it is such a powerful way to bring those two things together. Those are two different worlds. It's amazing. I’ve always been a child of the arts. I was an artist as a child. I’ve always loved them and been very passionate about seeing the artists in the business world and the science world together in a convergence.

What kind of art do you do? What did you do?

I was a painter. I did a lot of drawing when I was younger. I put away all that stuff. I was a pre-med major then I went into business.

You might have your moment where it comes back. The full circle arc on this from the beginning of our conversation is the first workshop I did with Sam Abell in Santa Fe where we were teaching together. We were meeting the day before the workshop. He looked through my portfolio and he said, “Hal, you need to stop using your telephoto lens. You need to start getting dangerously close to people.” I ordered that day a wide-angle lens and it came the next day.

After three days of doing the workshop, the third morning, I get up early. I go down to Santa Fe central town and an antique car show shows up unexpectedly. I’m intrigued by this car. I get behind it. I’m trying to do everything Sam taught me of composing the frame and waiting for something interesting to happen. I was behind the car looking through the back window, through the front window, waiting for something interesting to happen with that framing, looking through those two windows in the front. I took close to 70 photographs. My eyeglasses broke by the end of it. I was sweaty. It was Santa Fe and I was almost ready to give up, and this voice behind me said, “You might get better photographs if you get inside the car. Would you like to get in?” My instinct was yes. My shadow question turned around and said, “No, thank you.” I was trying to be nice to him. I didn’t want to intrude.

After three days of doing the workshop, the third morning, I get up early. I go down to Santa Fe central town and an antique car show shows up unexpectedly. I’m intrigued by this car. I get behind it. I’m trying to do everything Sam taught me of composing the frame and waiting for something interesting to happen. I was behind the car looking through the back window, through the front window, waiting for something interesting to happen with that framing, looking through those two windows in the front. I took close to 70 photographs. My eyeglasses broke by the end of it. I was sweaty. It was Santa Fe and I was almost ready to give up, and this voice behind me said, “You might get better photographs if you get inside the car. Would you like to get in?” My instinct was yes. My shadow question turned around and said, “No, thank you.” I was trying to be nice to him. I didn’t want to intrude.

Sixty seconds later, I was like, "He was being nice. He’s wanting to let you in." I turned around, “Is it okay? Can I get in?” He’s like, “Sure, come on.” He went around and let me in. It was a different view, sitting in the back seat of that car. Very short back seat, I’m tall, scrunched, sitting in. I get framed so that the front window, the side window, passenger and driver is showing and I hold still. I wait for something interesting to happen. About fifteen minutes later, this guy shows up. He pokes his head on the driver’s side. His wife pokes her head on the passenger side. They both poke their heads in closer. I’m not going to move because I want a fun shot. He says, “Do you come with the car?" I’m like, “No,” and I’m trying to hold my camera still.

It’s one of the most beautiful photographs I’ve taken. It was a beautiful moment. A touchpoint and one of those powerful moments because right there, I was dealing with my shadow. I had noticed it. I had put it in its passenger side of the driver’s seat of the car of my life. That moment of being committed to someone else’s world in their car, combined with letting go of my shadow, allowed me to have an experience of connection to another human being in a way that never would have happened otherwise.

That story is powerful because it got me thinking just that. It's this element of when you open yourself up to those experiences, when you allow yourself to break free from those things that are holding you back, a whole new world opens up, a person’s world. That experience touched me because of the fact that that’s a lot of the coaching experiences that I’ve had. You were allowing yourself to say, "If I could just stay at the surface, I can find out what is going on for them." You want to work on executive presence. That’s fine and great, but what’s really in your heart. What do you want? If I’m willing to open the door to that car and get inside, I could find out what that person wants for themselves and help them to uncover that. That story connects with that for me. Thank you so much for sharing that.

That reminds me of Oprah Winfrey’s fundamental question in life in all her interviews. It is, “What is your intent?” In other words, what are you solving for here? I could tell by your response to Parker Palmer earlier, in his, Let Your Life Speak book, he has this powerful story before he goes into this horrific depression, and that’s a whole different story. He has this powerful moment where he was still not sure who he was. He was chasing somebody he wasn’t and had applied to be the president of a university. Here’s why. He wasn’t sure whether he should take it because they offered him the job. He had learned a quicker practice of a clearing committee where you ask a few select people whom you fully trust to join you for a few hours.

They ask nothing but questions of you and you answer their questions, but they cannot answer you. They’re asking you questions. They’re trying to get to this point of, "What’s your intent, Parker, of getting this new job, of taking this role of the university’s president?" They asked their questions and then they got down to, "Parker, tell us why you want to take this job." He started giving them all these reasons why he wouldn’t want to do it. They’re like, “No, Parker. Why do you want to take the job?" There was this long pause of silence and Parker finally says, “To get my picture in the paper.” It was quiet in the room and they couldn’t laugh. That’s part of the rules. One of the people finally asked the question, "Isn’t there a better way to get your picture in the paper, Parker?"

I could tell you multiple moments in my life when they’re the difficult moments often. At the end of the day, I was being just like Parker Palmer, trying to get my picture in the paper in one form or another. In that book, Let Your Life Speak or A Hidden Wholeness, there’s a story that Parker shares from a Jewish rabbi. I think his name was Zusha. The story is when Zusha dies and goes to heaven, God will not ask Zusha, "Were you Moses?" He will ask Zusha, "Were you Zusha?" That to me has always stayed. That’s the constant tension in life between the shadow pulling us into being somebody that we had to be for somebody else in a moment when it was necessary. For me, it’s with my dad to a keystone or light energy-filled place which is totally different.

I can have this conversation for hours.

Create a safe space where truth can manifest your words.

You’re so good at asking questions.

I have one last question for you. What are 1 or 2 books that have had an impact on you and why? We’ve talked about a lot of books in this. We could pack a library full of what we’ve already discussed but if there’s anything else you wanted to mention.

I have a Christian-based faith and I’ll be honest, I’ve studied the life of Jesus Christ a lot. I love the gospels which are not perfect. They’re historical. They have inaccuracies. I get all of that but he did live and whether you believe in him as a God or not is irrelevant to what I’m going to say. It’s that if you look at what he taught and what he did like Buddha or Muhammad or fill in the blank, he was exceptional at asking questions. I haven’t gone to the point of, “How many? What was the question-answer ratio?” His was 1 to 9. It was one question for every nine recorded statements. To me, going to that story of his life is always a reflective grounding point for me around how do we ask the better questions?

Part of that is getting in situations where you are going to be wrong and uncomfortable and reflectively quiet, which he was so good at doing. Even giving himself space. "I’m going to the mountains, folks. You’re not going to see me for a while. I need my space." There’s a lot of stories in there around that. For me, that is an anchor point in my life. The second book I mentioned earlier, which is that series of books by Parker Palmer. He changed the way I did and always will navigate through life. His notion is, how do you create this safe space where truth can manifest itself? That's his words.

I use where inquiry can lead to insight and insight impact, but it’s where truth can manifest itself. Not truth with a capital T. It’s just your truth. How can it manifest itself? How do you create that space? You didn’t ask for this, but there’s a marvelous Jewish writer, Chaim Potok, who wrote a series of novels. The one I started with was My Name Is Asher Lev about cultural conflicts and identity on who am I and how do I deal with all of this. It’s a powerful series of books. Mary Parker Follett, I ran into her in my doctoral program. She was a consultant to the business, government, industry, labor unions in the early 1900s. As a woman, she’s hugely influential within that community. I read every word she wrote. She also reframed the way I look at the world. She talks about circular reciprocity, constructive conflict. She was a century ahead of her time. She was an anchor point.

The final person is not a book but it’s a person. His name is Bonner Ritchie. He changed my life when I was in graduate school. I’ll never forget halfway through his class, 2:00 in the morning, finishing a paper for his class, pushing away from that ugly red apartment furniture couch in my typewriter. This was the typewriter days and saying to myself out loud, "I don't care what Bonner thinks. I learned some important things here." It was the first moment that I'd broken through that, “It doesn’t matter what he thinks.” Bonner is so off the chart at learning, questioning, inquisitiveness and being a decent human being. When I finished a two-year program, we were cleaning up our apartment to move on to graduate school to get a PhD. Saturday, 8:00 in the morning, we got a knock on the door. Full Professor Bonner Ritchie is standing there at the door with a bucket, plastic gloves, cleaning tools, "How can I help?" That’s just who Bonner is. He pushes your mind to the edge where you think is possible. He causes you to rethink every assumption that you thought was important in your life. Underneath that is this teddy bear of service and goodness that shows up at the door like that. He’s my hero.

There’s something about being challenged by somebody. You hate them at the moment but then you love them forever in the end. It's what it is. I can think of a few people like that in my life. I don’t even know where to begin to close this out because we are at the end of our time together, but this has been such a powerful hour together with you. Thank you for the stories, the insights. I just went through a master’s class with you. This is amazing. Thank you for everything.

I want to honestly reciprocate that gratitude. I could see it in your eyes and I could feel it in your voice. You had created a safe, honest enough space for us to have the conversation we just had, and that’s a unique gift. I give you honor for that. This has been one of the best parts of my 2021, just an hour talking with you. Thank you.

It’s the biggest honor I’ve received. I’m going to take it back. It’s fuel for my journey. I want to give people an opportunity to find out where they can find out more about you. What’s the best place for people to reach you?

HalGregersen.com is the best place. If you go to About Hal there, you’ll see a lot of quirky elements of my own story. For those who are interested in the question burst, we just finished a beautifully done graphic illustration that has music and a voiceover around the question burst process that in four minutes, you can learn really fast, "How do I do this?" All you’ve got to type in is Question Burst Toolkit on YouTube and you’ll find that as well.

I’m going there next.

I hope it makes a difference.

Thank you again, and thank you to all the readers for coming on the journey. I know you learned so many great things. Go out and buy Hal's book because it's such a brilliant book, Questions Are The Answer. That’s it. That’s a wrap.

Thank you.

Important Links:

- Hal Gregersen

- Innovators DNA

- Questions Are the Answer: A Breakthrough Approach to Your Most Vexing Problems at Work and In Life

- The Innovator’s DNA: Mastering the Five Skills of Disruptive Innovators

- To Know as We Are Known

- Let Your Life Speak

- A Hidden Wholeness

- On the Brink of Everything

- Sam Abell

- My Name Is Asher Lev

- Question Burst Toolkit – YouTube video

About Hal Gregersen

When I look into the eyes of our grandchildren, I see pure wonder reflecting back: They’re hungry with curiosity about the world around them, unafraid to explore, and eager to discover something new each day. The gift of inquisitive creativity is something we were all born with – and something I believe we can sustain – by the simple act of questioning.

When I look into the eyes of our grandchildren, I see pure wonder reflecting back: They’re hungry with curiosity about the world around them, unafraid to explore, and eager to discover something new each day. The gift of inquisitive creativity is something we were all born with – and something I believe we can sustain – by the simple act of questioning.

As author, motivational speaker for diverse, globalized corporations and events, and former Executive Director of the MIT Leadership Center, I’ve dedicated my personal and professional life to this core questioning philosophy. And today, I’d like to share this inspired work as you explore the website. Experience why questioning is so crucial to building a leader’s innovation capacity. See how it is transforming the future of learning . Learn how questions can make the world a better place . And be sure to share your own thoughts, stories and questions along the way.

We may not be able to turn back the hands of time to childhood. But if we never stop questioning, we never risk losing our own childlike sense of wonder – and power – to disrupt the status quo.

Happy Exploring!

Love the show? Subscribe, rate, review, and share! https://www.inspiredpurposecoach.com/virtualcampfire

0 comments

Leave a comment

Please log in or register to post a comment