Making Beautiful Music Together: Michael Hendrix And Panos Panay Talk Collaboration And Creativity

Collaboration and creativity can create some strange yet wonderful partnerships that produce great art. Many of the greatest pop music hits, for example, were created in tandem by musical titans. And in this episode, our guests will help explore the intersection of collaboration and creativity. Tony Martignetti sits down to discuss things with Michael Hendrix, Partner and Global Design Director of IDEO and his collaborator, Panos Panay, Co-President of The Recording Academy. Both men talk about their unlikely meeting, the friendship that blossomed, and the collaboration that spawned a book. Find out how collaboration, creativity, and respect can become the bedrock of success.

---

Listen to the podcast here:

Making Beautiful Music Together: Michael Hendrix And Panos Panay Talk Collaboration And Creativity

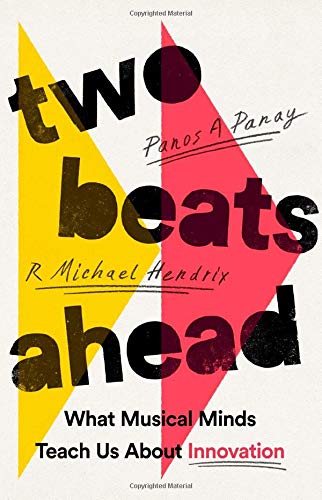

It is my honor to introduce you to my guests, Panos Panay and Michael Hendrix. We have two guests. They are both entrepreneurs, musicians and co-authors of Two Beats Ahead: What Musical Minds Teach Us About Innovation. Michael is a Partner and Global Design Director at IDEO and an Assistant Professor of Music, Business and Management at Berklee College of Music. Panos is the Co-President of The Recording Academy, and a Fellow at MIT Connection Science. He’s also the Founder of Sonicbids, a leading platform for bands to book gigs and market themselves online, as well as Cofounder of the Open Music Initiative. I want to welcome you both to the show.

Thank you, Tony.

I know we’re going to be having some fun. Thank you both for coming on the show. This is going to be a lot of fun. You both know how we roll. For the audience to know what’s going on, we try to share the story of what brought you together and what your journey was in becoming who you are through what we call flashpoints or points in your story that ignited your gifts into the world. Along the way, we’ll stop and see what’s showing up and follow the themes. What I want to start with is what drove you into your collective fields? I’ll start with Panos and then we’ll head over to Michael.

I’m sitting in my living room in Nicosia, Cyprus which is where I grew up even though I’ve spent many years in America but COVID has that all kinds of unexpected gifts with it. This has been one that I got to spend 2020 in my home country. My first musical memory is watching Elvis Presley in a movie called King Creole. The eponymous song called King Creole blew my mind, the baseline and the vocal performance. That trio that Elvis had with D.J. Fontana and Scotty Moore is amazing. That set me in many ways on a lifelong quest of wanting to be music, perform music and be close to music in every way that I can. Fast forward to my teenage years, I ended up applying and got accepted into Berklee College of Music which is good because I didn’t have any plan B.

I went thinking that I would be the next Eddie Van Halen but it didn’t quite work out that way. I ended up doing music business. I became a talent agent for a lot of artists that I grew up admiring like Nina Simone, Leonard Cohen, guitarist Pat Metheny and many others. Through that, I got the inspiration to start my company, Sonicbids. I ran that for thirteen years as the CEO. I sold it in 2013 and stayed on for about a year. After that, I went to Berklee where I founded the Institute for Creative Entrepreneurship. One thing led to another to my position as Senior Vice President in charge of overall institutional strategy in our global footprint.

How interesting it is that some people listen to music and they say, “This is great.” I like that Elvis Presley had a nice impact on you but sometimes music has this element of hitting you at the right moment and changing everything. It’s like the signal to noise. It completely cut through all of the things that were going on in your life. It has a lot to do with realizing that your calling is somewhat hidden in that note. Did you know at that moment when you started listening to that music at that age, “This is truly it. My life will always revolve around music?” Were there any doubts along the way?

We are a product of our environment that does make us categorize things.

I had several detours through the land of what we call football or in America, we call it soccer. I've always been caught between those two passions. It feels like another era as in 100 years ago and not 40 years ago. My uncle had a record shop. I remember going and flipping through all the records, seeing Roxy Music and Olivia Newton-John, all the records of the ‘70s and being so fascinated by the artwork, Ziggy Stardust and all those cool record covers. For some reason, Elvis caught my imagination. He represented so much more than music. It also set me down this lifelong love affair with America. I thought as a young kid that he embodied this spirit of freedom, rebellion, expression and coolness which was captured in one human being that embodied so much of my perception at the time of what America was. I caught the bug. I wanted to get a guitar. I ended up getting a mandolin.

Eventually, I managed to get an electric guitar. I obsessed over early U2, Van Halen and about every piece of music I could get my hands on. I grew up in a very different time where it wasn’t easy to get access to all this stuff because Cyprus was a small, isolated island. I got most of my musical experiences through the British Armed Forces Radio here called BFBS. That’s where I heard Zeppelin and Duran Duran for the first time. Back then, it was impossible to hear both back-to-back because radio here still to this day is not formatted. It’s whatever the DJ wants to play. It’s Austin. Even now I drive my girls to school every day and you go from a Zulu song to an Italian Eurovision metal winner to all kinds of Jamaican pop.

I love the idea of a soundtrack to your life. When you think about all the different genres, you’ve made through and navigating your path to creating the soundtrack that became your life through the musical genres. That’s neat that you’re sharing that. I want to shift gears and go over to Michael and have him share his story of how he got into the world of music.

I don’t remember a ton in my life where music wasn’t present. My dad loves to sing. His dad loved to sing. My dad was always involved in choir or leading singing at church. My mom played organ and piano. It was always around. I had to take piano lessons when I was young. I didn’t enjoy it but there are things I did enjoy. I learned about harmony through church singing. I noticed that my dad would sing the baseline or the baritone instead of the melody of the song. There are things that I picked up on as a kid. When I finally got to the point where I convinced my parents that I didn’t have to take piano lessons anymore because I despised it so much, I immediately picked up an acoustic guitar that was sitting in the corner of the house for years that I never saw anybody play. I started playing Ramones’s songs. That was the first band I’ve started to try to play on the guitar and R.E.M. Two different types of guitar playing. For me, that was part of it. Interestingly though, I never thought of music because it was just a fabric of life. I never thought it related to my career in any way.

I went into the design instead. I was pretty ignorant and even taking art classes in high school. I thought Industrial Engineering was industrial design so when I declared my major I didn’t realize I was signing up to Design Waste Sewage Systems. I quickly had a moment during my freshman year of college of realizing that was a huge mistake. I moved into design. A career in design also had my personal pursuit of music throughout for different bands, playing with people, helping run youth clubs and booking shows. It wasn’t until I met Panos a few years ago. I was asking him like, “How did these things come together?” It wasn’t me doing design, maybe some packaging for some music or playing in the band and doing some posters anymore. I was asking, “If I’m in an innovation field and I’m using design to improve healthcare, the immigration experience, tennis shoes, why couldn’t I use that to improve music? Why have I shut that out as a possibility?” He did not have an answer for that but it was the question in my mind when I met Panos at an Innovation Conference. In some ways, he would use different words but he was asking the opposite question of what can music do in design. It was the two of us coming together asking this question. At the same time, it led to us collaborating together.

I love the way you shared that because there’s an element of you went into this place of design and thinking that it was one thing. If you kept on following that breadcrumb into something else and being open to accepting something else, that’s what ended up to where you are now. There’s a weaving of those two worlds that is beautiful, the design world and art, then seeing that they can also add even more outside of that. It’s like 1 plus 1 equals 11 and then some, which is neat.

It’s through academia. There’s nothing wrong with us but we tend to compartmentalize all these subject matters. That’s how you become an expert in something. Our lived experience is never compartmentalized. It’s almost comical that both Panos and I could live this long and not have seen the connections between the two things. We are a product of our environment that does make us categorize things. At some point, your lived experience is mature enough that you can look back at things and go, “I’ve been doing this my whole life, I had no idea.”

Something that I constantly see. It’s this element that the environment shapes us into who we are. At some point, we start to challenge the status quo like, “I don’t have to be this way. Just because I’m in this field doesn’t mean I have to always be thinking this way.” I think about it as being in boxes. We put ourselves in these boxes of, “I’m doing this so therefore I am always going to be known for this particular discipline or specialty. That means I can’t cross over.” The reality is everything’s fluid. We can create whatever we want. When we start to see that beautiful intersection between other things, it becomes something that seems limitless. When I read your book, I see this through the lens of what you created, I thought of a lot of this world of business that I’ve come from.

Something that I constantly see. It’s this element that the environment shapes us into who we are. At some point, we start to challenge the status quo like, “I don’t have to be this way. Just because I’m in this field doesn’t mean I have to always be thinking this way.” I think about it as being in boxes. We put ourselves in these boxes of, “I’m doing this so therefore I am always going to be known for this particular discipline or specialty. That means I can’t cross over.” The reality is everything’s fluid. We can create whatever we want. When we start to see that beautiful intersection between other things, it becomes something that seems limitless. When I read your book, I see this through the lens of what you created, I thought of a lot of this world of business that I’ve come from.

I’ve dabbled in a lot of different areas myself, but the world of business needs to be challenged the way that we think. Using a different lens of the business world, of how we challenge and look at problems is important to take a different fresh perspective especially in these days and times. I want to talk about how you decided, “We’ve got to do something together?” What was the moment that you decided, “We’ve got to do something?” Panos, I’m going to kick it back to you and see if you wanted to share the moment that brought you both together. At first, I’m sure there were some challenges to collaborating.

Michael and I met at Innovation Conference. We were both scheduled to talk. After my panel finished, we met backstage. We had this connection like two creative beings. What’s interesting is I’m not necessarily sure if we made a conscious decision, “Let’s do something together.” I distinctly remember meeting Michael and he had come ironically to Cyprus. I remember getting an email from him in my inbox. The email you get when you meet somebody, “It was great meeting you.” It’s always fascinating because how many of those emails do we get that we missed or failed to respond to because our inbox is so full? I always feel you meet people, get a business card, go back to your office, usually send it there. The difference between picking it up and sending somebody a thank you note or leaving it there can change the trajectory of your life forever. I’ve always had that and felt that. It’s like this magical act of sending this message to the universe and one day you get an email back from that person, then there’s a connection.

It’s always this pivotal point. There was never an express objective of getting together. We were curious about what each other was doing, me at Berklee, Michael at IDEO. Looking and reflecting back on the way that our relationship and friendship have developed over the years, what was striking is that we are friends in the way that you meet a childhood friend. You meet somebody kicking about a football or you go to the beach. You don’t have an agenda. You are best friends when you were a kid. I had a get-together with my friends who I grew up with here. They don’t even ask me about what I do. I don’t care. There’s no objective other than to hang out with each other. Nobody cares about what you do or about your job. They are just there because you are who you are. That’s the way it was with Michael. We were both curious about each other and what we were doing. I’ve had the connection with Michael in the same way that I’ve had with a childhood friendship only we got to know each other in our 40s.

You had this almost instant connection. Luckily, that email was answered and you came together. Gradually over time, you’ve come to this place where you’ve said, “We’re going to do this. We’re going to get something going on. We’re going to make something happen together.” One of the things that I’ve realized about partnerships is that there’s a complementary skill. There’s one person who balances the other. Is that what you found or is it just that you’re two very similar souls who seem to come together and it works out well? Do you find the yin and yang to you that combine to make a powerful combination?

We have different skillsets. There are different things each of us does. The interesting thing is I don’t think about working with Panos in that way. I don’t think I have a role and he has a role or that I do this and he does that, even though it’s probably true. There’s something about that to me. It happens a lot in work relationships or even personal relationships. It feels a little bit like score-keeping to me. I shy away from that. I feel like a good relationship is not interested in keeping score. It’s interested in what can be. The way Panos and I worked together is we’ve always been interested in what can be. We’ve never made plans. We start a conversation like, “This seems interesting.” It’s almost organic. It’s more often than not. This is true. I haven’t thought about it. In many cases, it’s either Panos started something, he’s like, “Michael, do you want to come along with me and do this?” I’m always like, “Sure.” I go along with it, not knowing why but believing in that is interesting because Panos thinks it’s interesting.

A good relationship is not interested in keeping score. It’s interested in what can be.

There had been a few things where I’ve invited Panos saying, “Come join me for this.” Something clicks for him and then we move on. In our book, we talk about collaboration and collaborative relationships. In particular, there’s a short story about Beyoncé and Jack White working together. Beyoncé says, “Jack, I want to be in a band with you.” That's a good illustration of what I'm trying to describe between Panos and me. It’s not like one of us is having an agenda or setting the vision for the other and asking the other to follow along like, “I have this idea. You do this with me. It will be great. I’m the brain. You’re the brawn.” It’s more two people, shared collaborators coming together to make something. That’s what I appreciate about the stories about Beyoncé or Björk as well in the book who thinks about collaboration as a merger. There’s a point in which you don’t know who’s responsible for what. That’s perfect because something new emerges from that. That’s the musical mind. This is the funny thing. Panos and I have written this book but it’s certainly because we’ve lived this life and recognized it. We've had the joy of being able to talk to the other artists who had similar experiences about it. We thought, “Can we share this with other people?”

This is exactly the insight that I’m enjoying because there’s an element of this that’s like improvising through jazz. It’s like, “I’m going to throw this beat down or this note. Let’s see what pick up from this and what opens up from here.” There’s not a clear plan as to what we want to create. The options are open. It starts with someone having the passion and the courage to make that first move and then the other person be willing to say, “I’m open to that. Let’s see what happens. Let’s improvise and see what transpires,” which is a cool way to innovate as long as you have some boundaries set around. “What are the constraints that we want to live in?” I love the whole idea of the improv piece. It’s almost like that, “Yes and.” You drop down, “Here’s an idea,” and then someone comes in and says, “And we could also do this.”

Generally, Michael and I get involved in things that the other one does almost because we’re like, “If he’s doing it, it must be something interesting. Why not? I’ll join.” With stuff like that, I invited Michael to come and speak at the very first class I ever taught. He’s invited me to a bunch of events at IDEO. We’ve done a bunch of projects together where Berklee hired IDEO around specific projects. Michael teaches at Berklee. We created both the course on which the book is based, as well as the minor. We’ve launched. It’s funny because I’m the Cofounder of Open Music Initiative while the other Cofounder happens to be Michael. We launched the Initiative around identifying music rights holders using Blockchain. I’ve been invited to go and speak in Israel. I’m like, “Do you want to come? Maybe you’ll do your thing. I’ll do my thing.” We’re almost like a traveling band. We were going to go and do something else together that’s unrelated to what either of us is doing for our day jobs and even the book. That’s the fun part. We’re both biased towards, “Yes, why not?” Many times, we edit stuff like that when we’re faced with options and decisions.

Along this trail of creating this amazing collaboration, where has it that you’ve hit roadblocks or challenges along the way? Maybe there were some moments that you felt like, “Is this right for us?”

It’s the book. This was a classic example of what I said. The agents had originally approached Michael to write a book. Michael said, “I don’t have time but talk to my friend Panos.” I’m this sucker who says yes to everything. I started writing the book. I’m like, “I can’t do this on my own. It will be so much more fun if Michael comes on board. We’d geek out together about all these musical joys we share.” At any point during those three years, we’ve had multiple false starts and times where I got frustrated. I shut down. I couldn’t write and there are times where Michael got frustrated. There were many points where either of us or sometimes both of us decided we should walk away. We’ve asked for an extension from our publisher. We were like the temperamental rockstar who goes into a studio and spends way too much money trying to perfect the drum sound.

I’d love to know your thoughts on this Michael too. What you’re describing is exactly what your book is about. It’s the struggling process of being creative working together. Creating the book is a collaborative process of getting to create people working together. If you are out of sync or not feeling the same way, it can be challenging. It’s challenging to work together with people and collaborate even when you get along.

Creativity is hard, especially to be good at it. It’s not hard to come with a lot of ideas but it’s hard to get them to good ideas and then to great ideas. There’s a book about Demoing. We use a Justin Timberlake quote, “Dare to suck,” which is this idea that you’re going to be vulnerable enough to share ideas early. The reason you do that is you want other people to be able to respond to them, hear your intention and then build on that idea. It’s the yes-and concept you mentioned. In our collaboration in writing a book, we have those moments where if you embrace it as an iterative process and you are like, “This thing didn’t work,” but it made you pivot this direction and now you’ve got something new, then you pivot again. It’s still painful and hard but it’s not a blow to your ego. You’re not saying, “I failed.” I don’t think either of us ever saw even those hard moments in the book and writing the book. Perhaps it could have been a dark second where we’re like, “This is the end.” Neither of us is like that.

We didn’t believe we were going to quit. We knew we were going to push it toward the end but we knew it was also hard. That’s part of it, having to stay committed to the process. That’s one thing I appreciate about the Demoing chapter is it talks about the value of sharing early, being vulnerable, embracing iteration and experimentation. If you can embrace the process and recognize the creative process has friction, it is difficult but also a commitment to a result in something new, you can keep going. A fault a lot of people make is when they’re pursuing something new, they expect themselves to be experts early on. They judged themselves as if they were judging someone that’s been doing the same thing for a decade. To everybody reading, can you draw? It’s one of those terrifying questions. Most people are like, “I can’t draw anything.” The truth is everybody can draw. Some of us can draw better than others. The good ones have done it a lot more. It’s the same thing about singing. Honestly, I’d never written a book. There was that for us to learn. It’s one thing to write essays or articles for an online publication. It’s a whole other thing to write a book with 80,000 words. That’s a journey that we had to go on.

It’s exactly why social media is wired for us to be looking at. We see people as a snapshot of where they are at any given time. They’re sitting on the beach, counting their 20s or 100s. You see that and then you think, “They’ve made it.” You haven’t seen the endless nights, days and years it took to get to that place. You just think that they showed up that way. The important thing is you have to start somewhere and start to show up and continue to do the work. By doing and committing to that work, you’ll get there. There’s no fast pass.

It’s hard work. We would argue, best not done alone.

There’s a power in collaborating with the right person and finding the right person who challenges you to be the person you’re meant to be. From the vibe I get from you guys and from what I’ve seen so far, you do bring out the best in each other. Would you agree?

We do. It's interesting because, on the surface, we're not that similar as people. Michael tends to be more introverted. I’m more extroverted. Michael comes from Tennessee. I’m from a Mediterranean Island. I spent most of my life in music. Michael spent most of his life in design. We have the commonality of music as a shared passion but that’s not it. It’s been interesting because both of us have an open mind like, “Let’s see where this goes.” We trust that each other will brings something of their own and something unique to the table. It’s not about keeping score. There were probably times during the process of writing the book where I hit a wall, either because I was busy with work or because I was traveling all the time and Michael carry the load. There were other times where I was able to deliver.

There’s never been in all the time that we’ve known each other, I never thought, “I’m doing all this and Michael is not doing that.” Hopefully, Michael never felt the same way. It’s that trust that exists in ultimately any good collaborative partnership. I’m proud of Two Beats Ahead because I see how people are responding to it when they’re reading it. I feel that we wrote the book that I would want to read. I know it sounds silly but that was the benchmark for me. Can I write something that I would care to pick up every night I go to bed and can’t wait to finish it versus something that just sits on your shelf? You bought it because you’re trying to be nice, but you can barely get past page six. We make it easy to get past stage six. I wouldn’t give it up to the audience. Even if you can’t read, you can still get through page six.

Creativity is hard, especially to be good at it.

We did have a story about the breakup of The Beatles. The productive years of The Beatles were no different than what we’ve been talking about in terms of Panos and I writing the book. It's an incredibly fruitful short period of time like seven years, but then the Beatles did break up. They got to a point where they went from having a shared agenda to separate agendas. That’s the point. You can blame any one of them. A lot of people like to blame Yoko which is unfair. You can blame any one of them for pursuing their own agenda rather than having a shared agenda. That’s the other thing to think about in any of our collaborations. Panos and I have a very loose shared purpose that’s been good for us. We haven’t had to define that so tightly that we’re either in or out of it. That can be a huge contributor to whether people choose to continue to work together or not. It’s something to think about.

I spoke to Steve Marker, one of the multi-instrumentalists from Garbage. We were talking about the band dynamic. He said, “By the time I got to Garbage, Butch Vig, myself, Shirley, we’ve all been in a lot of other bands that didn’t work. Egos were in the way. The drummer didn’t show up. If you think Garbage is something special because we’ve been together for many years, you also needed to hear the story of the fifteen-plus years before in which nothing worked with the other bands that we were in until we all had this shared agenda. We clicked and started to recognize what worked for us.” That’s another component to it as well. Probably the fact that Panos and I did meet in our 40s, we already had a good twenty-plus years of careers behind us. It has made our collaboration easier. If we had met when we were in our early twenties, there would have been a lot to figure out because we were trying to sort ourselves out and understand what collaboration means.

I love this because there’s an element of having prepared yourself for the opportunity to meet. You’ve been able to go through a lot of the trials and tribulations already in your career. You’ve been burnt before potentially. You’ve had your series of upsets, letdowns and successes. You’ve had a range of those things before coming together. When you’re coming together, this is your opportunity to be like, “Let’s be open to seeing how we can get this right together.” That’s part of the lesson for the people who are reading. Before you decide to jump in and have a partnership, be careful about who you’re getting into the partnership with. Maybe test it out. Get some experience under your belt before you start jumping in and having collaboration with somebody else because it’s going to test you.

The trick is not to put a lot of conditions on it. It’s like the Jack White and Beyoncé story. Neither of them had a song in mind already written that they were taken to the other. There was a belief that something great would come out of that. You have to have that kind of optimism that something good will happen. It’s not well-defined but amorphous enough that the belief in the outcome is what motivates you. Not a definition of the outcome.

It’s like the old saying in Buddhism, the detachment outcome. When you believe something will happen, how you get there is different. Being open to how it shows up is different. When you started to write this book, what was the real call that you wanted? What was the mission behind it? Maybe it was the mission you have right now. What do you want for people when they read this book?

We want to stimulate a conversation about the immense value that creative education and orientation have. We feel that in many ways over the years, there had been a lot of discussions about the importance of science, technology, data and how we got to teach our kids to be scientists, engineers, mathematicians and technologists. I have no problem with that. I have a tech background. Absent from the conversation is this concept of not having to choose between science and creativity or business and creativity but ultimately, all of these are creative disciplines. By learning how to imagine, emote, connect with people, all the things that a creative or even specifically a music education does, these are critical human traits that need to be cultivated in our young people. We should not see creative education as one that’s purely meant to be practically applied by somebody becoming a performer. It’s something that awakens the spirit, the mind and enables you to see possibilities that are unseen by most people.

There is a reason why most Nobel laureates tend to also have an artistic background in addition to their main discipline, a Minor to their Major. That Minor tends to be a creative pursuit. That was ambition and is the ambition behind Two Beats Ahead. It is to introduce a question. Can we or should we be looking at today’s problems using a different framework and the one that we’re presenting in the book? Our existing systems or existing frameworks of organizing our companies, our governments, and the way we manage people, do they still apply or is it time for us to rethink them? We argue that it’s time to rethink them. As Tim Cook said in an address to MIT graduates several years ago, I’m paraphrasing here but he said something like, “I’m less worried about robots thinking like humans. I’m more worried about humans thinking like robots.” Maybe we should have titled it Here Is How Not to Think like A Robot. We ended up calling it Two Beats Ahead. Maybe there’s something robotic in the title.

I wanted to get thrown into the room because there’s so much power behind that statement. The reason why the book is so powerful is because we do need this. This is a call to action of sorts. We need more of these initiatives at all levels. It means starting with school but all the way through to going into businesses and into different parts of society. I think about my own journey. I was an artistic child who moved into sciences and then eventually into business because I was told that it wasn’t going to be a path that would be lucrative. I complied.

That’s the way a lot of us grew up. My parents, I credit them for not preventing me from pursuing design as a career, but I wouldn’t say they supported my design career emotionally. It’s because they didn’t know. It wasn’t that they didn’t appreciate creativity. It was the same thing. They’re like, “You’re my child. I don’t want you to starve to death. Therefore, don’t go into the creative field.” We live in an era where a lot of the myths about creativity are not as true anymore. There are plenty of fields you can go into now and make a living wage. I’ll thank Apple for that. The proliferation of desktop publishing first and then subsequently all the other cool things we can do with laptops changed the workforce. If parents ask me, “Should kids pursue a creative education?” I will say yes. For the record, my kids are pursuing creative education so I’m living it.

What’s 1 or 2 books that have had an impact on you and why? Who wants to start?

I can kick this off. I’m a biography reader. I’ll mention three. When I was young, I read the biography of Bill Graham, who was a famous presenter of live shows. He’s instrumental in creating the whole scene in San Francisco in the ‘60s and ‘70s. He’s an iconic music promoter and an immigrant who escaped Nazi Germany and came to America. Bill Graham Presents is the name of the book. It’s what awakened my interest in the music business. The other two, one is Titan, which is a biography of John D. Rockefeller by Ron Chernow. It blew my mind. That was almost ten years later. The last one is a book that I read a few years ago, which is a biography of Muhammad Ali. I forget the author’s name. It got you to see beyond just the myth, the caricature of Muhammad Ali and see him as a human being and as a man. Even his own journey from Cassius Clay to Muhammad Ali, the conversion to Islam. That book changed my life. There had been three pivots. Each one of these books is presenting those pivots for me.

First of all, I haven’t read Muhammad Ali. The Titan, I have read a long time ago. It’s a big book but that’s a good recommendation. Biographies are powerful. It’s why I do this show here is to see how did that person become who they are? What are the throughlines that ran through their lives? I love that you share those three because they’re all amazing. Michael?

I’m going to share one. There’s a book by an author named Mason Currey. It’s called Daily Rituals: Women at Work. It’s the second of a book he’s written in a Daily Rituals series. It’s a collection. Usually, it’s 3 to 4 pages about a particular playwright, artist, composer from the 19th Century to now and what they did on a regular basis to pursue their art. One of the most fascinating things about this book is you realize that most of these people that we revere as great novelists, poets, choreographers. Most of them had to figure out how to pursue their art outside of their other responsibilities. They didn’t have the privilege to say, “I’m going to go sit in the woods and write all day.” They raised families. They help run a state.

One, it’s an amazing testament to the way society has changed. Two, it highlights the creativity of these women and the amazing way they could work through adversity on a daily basis to create the art forms that have changed the way we see the world now. I would recommend it for anyone that finds themselves struggling with saying, “I’m creative but I don’t have time to do X.” You’ll see that almost nobody’s had time to do X except the rich and famous, the lords of the manor. Everyone else had to sneak it in before sunrise, after dinner, during their lunch break and were still able to make great art. It’s a commitment to the process and to the love of what you do that will make you successful in the end.

It’s a commitment to the process and to the love of what you do that will make you successful in the end.

You’re probably wondering why I ask about these books. This is where the learning is too. It’s knowing that there are breadcrumbs that we leave for other people to pick up, to go grab these books and see where we continue the conversation through reading these books. It’s like reading your book. When we read your book, it's doesn't end with you writing the book. The conversation begins by reading the book. That’s the beauty of doing something like that. Thank you so much, both of you, for sharing your insights, stories and your brilliance. Thank you for doing what you do in the world.

Thank you so much.

I wanted to give you a chance to share where people can find you. Maybe you could give the website or wherever is the best place.

We have a website that’s called TwoBeatsAhead.com.

There you have it. Go pick up the book, check out their website and take this in. It’s going to be amazing for you, especially for those of you who are in the corporate world who want to embrace these insights and bring them into your teams and into your organization. Thank you so much. Thank you to readers for coming on the journey. That’s a wrap.

Important Links:

- Two Beats Ahead: What Musical Minds Teach Us About Innovation

- IDEO

- The Recording Academy

- MIT Connection Science

- Sonicbids

- Open Music Initiative

- British Armed Forces Radio

- Bill Graham Presents

- Titan

- Daily Rituals: Women at Work

- Daily Rituals – Book Series

About Panos A. Panay

Panos A. Panay B.M. ‘94, Co-President of The Recording Academy. He spearheaded the founding of the Open Music Initiative, which brings together more than 300 leading music, media, and technology industry organizations, and academic institutions focused on streamlining metadata and payment tracking for artists.

Panos A. Panay B.M. ‘94, Co-President of The Recording Academy. He spearheaded the founding of the Open Music Initiative, which brings together more than 300 leading music, media, and technology industry organizations, and academic institutions focused on streamlining metadata and payment tracking for artists.

Panay has been recognized in Fast Company's Fast 50, Inc Magazine's Inc 500, Mass Hi-Tech All Stars, and Boston Globe's Game Changers. For his work with Sonicbids, Panay was also profiled in the book Outsmart by best-selling author Jim Champy and spoke at the World Economic Forum at Davos, Switzerland, as part of his work with Open Music. He has been a guest on programs such as CNBC's "Squawk Box" and a guest writer about entrepreneurship for Forbes, The Wall Street Journal, BusinessWeek, Fast Company, and Inc Magazine, among others. He is a public speaker at many universities and events around the world. His first book, Two Beats Ahead: What Musical Minds Teach Us About Innovation, co-authored with Michael Hendrix of IDEO, was released earlier this year and was named as a business book of the month for April by the Financial Times.

About R. Michael Hendrix

R. Michael Hendrix is an American graphic designer, author and musician.

R. Michael Hendrix is an American graphic designer, author and musician.

He is a Partner of the influential interdisciplinary design studio known for consistent innovation and a keen ability to see the big picture and the smallest dot.

0 comments

Leave a comment

Please log in or register to post a comment