How To Use Your Failure To Succeed With Steven Lavine

You make mistakes and you learn. Enter Steven Lavine, whose story inspires you to keep doing the best you can despite failure. Not only that but to succeed because of failure. Steven was the President of the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) from 1988-2017.

In this episode, he shares with Tony Martignetti how he carried his mother's sense of failure from childhood. Her mother was a passionate pianist, but she failed to achieve the level of success she would've wanted. This sense of his mother's failure propelled him to bring CalArts to where it is today. If you're feeling downhearted because of your mistakes and you need a lift, this episode is for you. Tune in!

---

Listen to the podcast here:

How To Use Your Failure To Succeed With Steven Lavine

It is my honor to introduce you to my guest, Steven Lavine. Steven was President of CalArts from 1988 to 2017. After having an illustrious career through many different twists and turns before then, he guided the institute through a period of growth, program development, community engagement, and rapidly increasing diversity and international recognition. He led the $40 million rebuilding process after the institute was closed down by the North Bridge earthquake in 1994.

He conceived and guided the building of REDCAT, CalArts’ multi-disciplinary professional performance and exhibition facility in the Walt Disney Concert Hall Complex in 2017. He became the Founding Director of the Thomas Mann House in Los Angeles, where now he serves as the Chair of the Los Angeles Advisory Board. Thomas Mann House brings German and American thought leaders together around the challenges facing democracy in the world.

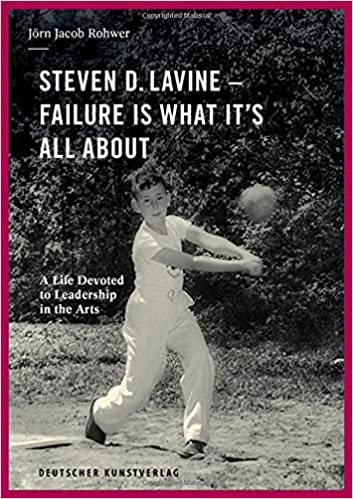

Quite a turn, he is a subject of Jörn Jacob Rohwer’s published book, Steven D. Lavine. Failure is What It's All About: A Life Devoted to Leadership in the Arts. He lives in the Little Tokyo section of Downtown LA and also has a house in Mexico. He has two dogs, Lola and Max. His wife is a writer and photographer as well named Janet Sternberg. She has a new book called I've Been Walking, which is a photobook taken during the pandemic.

---

I'm truly looking forward to digging in. Steven, I want to welcome you to the show.

I'm delighted to be here. I could feel the warmth of the campfire already.

There's something about sharing stories and bringing people's stories into the powerful campfire. It has been shared throughout since the beginning of time. What I love about this process is that we get to share what brought you to do all this amazing stuff in the world. That's what we are going to do. Steven, we are going to tell your story through what's called flashpoints.

These are points in your story that have ignited your gifts into the world. As you are sharing your story, pause along the way and we will see what themes are showing up. With that, I'm going to turn it over to you and you can start wherever you like. Some people start as early as their childhood but if you want to start wherever you like, it is fine.

Literature helps you understand that your unhappiness is part of the human condition. You're not alone.

I will start with my childhood because this book that you referred to that has come out was about me, traces those early influences and how they shaped who I became. I grew up in a little town in the Midwest, the first of 497 people in a town of about 23,000. My mother set out to be a concert pianist but didn't have the competence or the money for a career. My father, who grew up like my mother, very poor, ended up as a country doctor.

The key things in this are, one, I grew up hearing my mother late at night, playing piano in the living room and crying because she couldn't play as well in her 30s as when she was a full-time pianist in her twenties. While it didn't have an immediate impact, it had a lot of impact on my life but in the long run, it's what made CalArts so satisfying, helping artists have their careers. It’s a real key moment for me.

My father was someone who believed we are all alike. Fifty percent of his practice was people who didn't have anything organically wrong. They weren't happy in their lives. They needed someone to talk to. The country doctor was the person you could have a conversation with under the guise of tracking your symptoms. He raised me with this sense of how much we all share. I would say those two things, plus my own personal discovery as a kid in the arts.

I can give you two key moments there. One, Bob Dylan is a distant cousin. Before anyone had heard of him or at least I had heard of him, his uncle played my father and me a record of his. They said, “He's terrible. He can't sing. His brother is a pianist. He's the talented one in the family.” I heard it and it was blowing in the wind. I couldn't have told you exactly what it meant as a 7th, 8th grader but it felt like the truth. It taught me something about art and the world.

The other was, as a young person at our little local college, seeing a film by Alain Resnais called Hiroshima Mon Amour, the kind love affair set during the post-bombing of Hiroshima. I didn't even know what it was about but there was something about the tone and the pace that felt like, “This is what I'm looking for. This is the truth.”

I want to say, “There's something about this.” Two things that I'm noticing are that we are influenced by our parents in a big way. It's amazing when you can go on to be able to have that legacy that you have. That's founded on trying to create something that helps the people to who you relate your parents. When you hear your mother as the artist, you start to have this connection to the arts at a very young age and feel at a deep level what it means that art is emotion.

There's an emotion that gets a vote when you see something, whether it's beautiful in the sense that it's aesthetically pleasing, sometimes it's dark pleasing and it still evokes something in you. Hearing the story about your father, now I'm thinking about country doctors who were the first real therapists and listeners. They listened as a profession and that's an interesting insight I had never thought of it.

He was the old-time doctor where if you couldn't pay, he didn't expect you to pay. Once I remember, someone gave us a piglet to raise. This is when we lived in the tiny town, the Port of 97, not realizing that what you raised it for was that, you then would be taken to be slaughtered. That's how you pay the doctor. That was a shock when I realized we were raising this piglet to be slaughtered. Anyway, that's neither here nor there.

Before we continue with the story, I do have a question that's bubbling up for me now. At this age, did you have a sense of what you wanted to be as an adult? Did you have that clarity of like, “I want to be a curator of arts or an art historian” or whatever it may be?

I didn't. This town I grew up in Wisconsin was on the tip of Lake Superior, where it was winter for about eight months a year. I grew up basically curled up in a book reading. My father thought being a doctor was the best thing in the world. You’ve got to help people, respect in your community and got paid okay for it. I grew up thinking I have to be a doctor, even though I had no interest in the things that went into being a doctor, except that listening to patients. That was something I could imagine. In the end, by the time I went to college, I thought there were three things I could be.

One was I figured out I couldn't be a doctor. That was one of them. It seemed like an honorable thing to be you could do good. The second was to be a minister but I grew up Jewish, not knowing anything about being Jewish. That didn't seem likely I was going to be a minister. The other was because I had gotten so much comfort from literature when I was young, from reading books, was you could be a teacher and you could use literature to help people understand that their own unhappiness was part of the human condition that they weren't alone.

It's what joins us as human beings that we suffer many of the same things. Obviously, some people suffer terrible things. We don't suffer but we all go through otherwise the same cycles. Ultimately, when I abandoned being a doctor, it was an English professor I became. With as much an idea about it being a way to help people as it was the arts but it was, to me, driven by what to my mind was the purpose of the arts was an insight into our shared human condition.

When you think about that element it's communication, the ability to have a book or anything that's written down is a way to communicate something that continues to share emotions that are deeper for us. It connects conditions until you start pouring yourself into those books and sharing with others. That's how we communicate on that deeper level. That's cool that you went into this field and you are doing something that helps people. What happened now? What happens next? Did you do this for a while?

I went to Stanford and Harvard. I’ve got this job teaching at the University of Michigan. I won awards as one of The Best Undergraduate Teachers in the university. What I discovered was I wasn't a scholar and what was rewarded in the university was my own research. Research is often seen as people working together but in my generation, especially literary research was solitary life in the library.

Find polite ways to say no to people.

I found it tremendously lonely way to be that I wanted to be with the fact when I would write, I would go to a coffee house or someplace public and noisy, to have people around me, to get over the loneliness of what we were doing. At a certain point, I decided I had to do something else. This wasn’t it. I have had a lot of good luck in my life starting with my parents. I was looking around and I didn't know what else I could do. I’ve got this fabulous fellowship to go to in The Rockefeller Foundation, originally in a role called Visiting Research Fellow.

Basically, the idea was you could only be there for a year and be totally honest about what you thought of the programs because you could not get hired anyway. I discovered a much bigger world than I had been on than I had been occupying. Suddenly, I was researching for the foundation of African studies and how we might strengthen what we know about Africa video art. I always had followed contemporary art, even though it wasn't the main thing I was doing. I started a video art program. Along the way, I saw how unjustly the opportunities in this society are handed out.

I had a wonderful director of my division, a woman named Alberta Arthurs. We were one of the first University of Foundation Programs to focus on diversity. You could care about the contemporary but caring about the contemporary also meant caring about the diversity of the contemporary. I started a program that experimented and how you present art, not from your own culture in a museum setting.

I found it thrilling to be dealing at this juncture of, in a way, the social and the artistic. It couldn't accomplish anything socially unless it was artistically valuable and yet you were concerned that it had that opportunity to have an impact. I owe Alberta so much. She had been a college president and done a lot of different things. She understood about trying to have an impact. She also had started out as an English professor, cared about scholarship and getting the details right and teaching. She was always looking for what difference it could make in the world. That reinforced my desire to make a difference.

The theme here is there's an element of having an interest and desire to take the learning and the things that you are discovering but also making sure that it is put into action. That's the important thing that you are starting to see come up. I also see a lot of values that I wanted to check in with you. What did you learn about your values this time? I see curiosity, caring, impact, and fairness are some values that are very much being portrayed throughout all the things that are showing up at this point in your story. It seems like that's followed through all the way through your life.

In a way, you have all these complicated turns, surprises of good luck and bad luck. There is this through-line, which is you and what you care about. It's very fortunate when what you care about can be reflected in your work. Many people have jobs that they have to do because they have to support themselves but have no direct relationship to what their real values are. Not that it's against their values but it doesn't have anything to do with them.

It was never in my family about making money. It was always about doing something of value. Now that I'm living on my retirement income, I'm thinking maybe a little more or less than I'm making money would have been not such a bad thing, although I'm fine. The University of Michigan job, The Rockefeller Foundation, and then this astonishing thing, all while I was at the foundation, these alumni of CalArts, I don't know if your readers will know about CalArts. It is arguably, over many years, the most influential art school in the United States and possibly the most influential art school in the world or certainly in the European-American world.

Now a lot of people have learned from the CalArts way of doing things and there's competition. I kept running into successful alumni. Jim Lapine, who was Stephen Sondheim's collaborator and all their great musicals, painters and filmmakers, I could go on. After about seven years of the foundation, Alberta said, “You’ve got to go get another job. The only promotion you could have now is to have my job. I don't intend to leave anytime soon. You have learned what you could learn in this job. You’ve got to go out in the world. Even to do this job better, you have to take your lumps. You have to be someone who needs the money, not someone who has the money to give out.”

Now a lot of people have learned from the CalArts way of doing things and there's competition. I kept running into successful alumni. Jim Lapine, who was Stephen Sondheim's collaborator and all their great musicals, painters and filmmakers, I could go on. After about seven years of the foundation, Alberta said, “You’ve got to go get another job. The only promotion you could have now is to have my job. I don't intend to leave anytime soon. You have learned what you could learn in this job. You’ve got to go out in the world. Even to do this job better, you have to take your lumps. You have to be someone who needs the money, not someone who has the money to give out.”

I saw this advertisement looking for a president and I didn't apply because I thought, “Why would they hire me? I have never run anything.” I run a secretary but she was probably running me. Why would they look at me? I didn't apply. What happened was they had a search process in which, as it happens, turned out to be in deep deficit and danger of going out of business. It's a severe danger going out of business. In the first search, they came up with five businessmen as the finalists, a Vice President of the American Stock Exchange, a former Head of Western House, prominent business people. At the last minute, the search process works.

The search process was the deans and leaders of the various art schools at CalArts and the trustees. They decided, even if this was going to take radical restructuring if you didn't understand the substance of the arts, you weren't going to get that restructuring right. He couldn't do this just in process. They called off the search, went out and called a few friends of the institute. Martin Friedman, who was the longtime Director of the Walker Arts Center in Minneapolis and one of my heroes, deceased now, gave them my name and almost overnight, I ended up getting hired.

I remember one of the trustees saying to me, “I know you are the candidate I most want to go to a movie with but I don’t know if you are tough enough to do this job.” I remember saying to him, I discovered a certain something in myself in this process, “I don't know if I'm top enough either but at a foundation, mostly what you do is find polite ways to say no to people. If we are going broke, there are probably lots of opportunities to say no to people. I could probably do that part.” They took an amazing chance. They must have been desperate. My wife was also part of this process. She’s very impressive. I think they must have thought, “We are going to get 2 for 1 in this case. Maybe between them, they can do it.” We did it.

I want to pause for a moment to say that's powerful what you said earlier about being able to say no. It's great when you can find that inner courage to be able to say, “I don't know what I'm doing. At the same time, I'm willing to take this chance.” It takes courage to say no to people and to get clarity around the things that are right for this moving forward and what's not right. I will make mistakes along the way. I'm sure you did. What was probably at the inner core of all this, as you said earlier, was this desire to connect with that passion that you had for helping artists to create what they wanted to create.

We were living in New York at that point. My wife had lived in New York for many years. She was ready for something new. I was getting into the groove. We weren't sure we were going to do this. The search was done during the summer. When I originally went to campus, nothing was going on. The first time we walked into the building together and it wasn't a full flood, it’s just the energy and the passion of the people. I remember the University of Michigan and my time at Stanford. There were a lot of sitting around drinking coffee and shooting the breeze or maybe it was more serious of that. Maybe it was talking about the meaning of life in our own way.

To go to this place where everybody was driven, I remember the first provost during my time called A Paradise for Workaholics. I loved the fact that everybody had a sense of purpose. I'm sure there was some hiding out who didn't but the predominant thing was getting this done. One of the things that's nice about arts education is you learn in the arts. You have to deliver it. If you have an art exhibition or a concert, you can't say, “I want an extension. I'm not done yet.” You've got to get it done when you’ve got to get it done. That turns out to be not such a bad thing for education.

You have to deliver your task. You need to get it done.

It reminds me of the Seth Godin as they ship it. You get into this mode of getting out of perfection and move forward. Don't get too hung up on perfection.

In fact, this goes back to something earlier in our conversation, and then we will also go forward. That book about me, Steven D. Lavine. Failure is What It's All About is in part about the experience of my mother's sense of failure. My sense of failure was I’m supposed to cheer her up and I failed at it when I tried. I carried around the sense of failure myself. You get to be running an institution. You fail left and right. You make mistakes. You learn.

The first week, there was a wonderful world percussionist, John Burgerville, now deceased on the faculty. One of our big supporters was the Walt Disney company. I’ve got this call from Michael Eisner saying, “I'm hearing that you've got this faculty member's bad-mouthing the Disney company. I don't expect you guys to praise the Disney company but it doesn't seem right that when we are helping keep you alive, that someone in music who has nothing to do with what we are doing should be bad-mouthing us.” I didn't know what to do. I did the wrong thing. I broke into his classroom. I said, “I’ve got to talk to you.” He came out in the hall and I said, “You’ve got to not do this.” He quit on the spot. He ran a world-famous percussion program. I thought, “The first thing I have done is lose a valuable faculty member.”

I talked to this person who knew him well and said, “What should I do? Should I call and apologize?” He said, “No, John quits all the time. He will call tomorrow and apologize to you.” I learned from that not to act on your first impulse. My father used to always say, “If something is worth doing today, it will be worth doing tomorrow as well.” One of the dangers when you are surrounded by challenges, you rush into trying to solve them before you know what to do. You want to get rid of some of the problems, so you don't have to think about them and that's not a good strategy. You need to take your time and figure it out. I learned to slow down.

To my coaching clients, I'm always saying like, “Test the urgency.” There are some things that they show up, and they seem like they are so urgent but if you give it a night and come back the next day, you would be surprised. First of all, how much better of the decision you make and, whether or not it's even urgent in the first place?

I remember when I was a tutor at Radcliffe, there was a wonderful woman, Kathleen Elliott, who's the Dean there. She said, “When students come in and have a problem, I say, ‘When did you last have a full meal? When did you last get a night's sleep?’” Basically, she would send them home to have a meal and sleep, and then meet her the next morning. She said, “By the next morning, half the problems had disappeared.” I was surrounded when I first went there by people who there had been a long transition in which there had been only an acting president for four years, during which time the school had gotten into a deep deficit.

Some people were anxious. They were trying to keep their programs strong. They felt, “I’ve got to get to them now. I’ve got to get up to help us do X.” Since we were broke, I couldn't help much anyway, except to be clear that you were going to help eventually. That was a real lesson. If it's a crisis now, it is still a crisis tomorrow. It doesn't have to be solved now. How much that seems to be a crisis if you break it down? It's a problem but it's a solvable problem.

I want to fast forward a little bit to get into how you exit CalArts and into Thomas Mann? What did that transitional look like? It's quite a change. Maybe talk about the work you are doing there if that sounds good to you.

Let me put in one middle term. I'm sorry to go into such detail about some of this stuff. When I went to CalArts, basically almost the deal I made with the board is I will figure out how to solve this deficit problem and get us financially strong. In exchange, we have to become genuinely reflective of the diversity of America. It's a great school. We have had a great accomplishment but we are only serving some of the needs of the country and the world and we need to open this out.

In a way, that issue of diversity and social justice became the principle that guided an awful lot of my decision-making at CalArts. I remember reading a book about Harry Truman as president, which made the point that, “To be president, you don't have to be very smart because you're always going to be surrounded by people who are experts in what they do. What you need is to know what you believe and have some actuating principle that you could refer your decisions to even when you have incomplete knowledge.”

For me, that became diversity, equal opportunity and social justice. The reason I say all that is the average length of time of president last in America is down to 5 or 6 years. To serve for 29 years is a lot. I saw it in five-year increments. At the start of the last five years, I basically told the board at the end of this time, “I'm going to step down.” As much as I still love the job, I knew it was coming. I wanted to do something else with my life while I was still young enough to do it.

Just like CalArts came out of the blue, this opportunity in Thomas Mann, the Nobel Laureate from Germany, had lived in Los Angeles from 1942 to 1952 in exile from Nazi Germany. While he was in the United States, he became a US citizen and a Roosevelt Democrat. His home was being put up for sale as a $14 million tear me down. You could tell it was a tear me down because they only described the lot, not the house on the lot.

The German president, the idea that without any thought, the home where he had written two of his greatest books was going to disappear. He and the German parliament basically decided in three weeks to buy the house. To justify buying it, they described it like it was going to become a very big cultural center, even though it was a house. The neighbors got upset because it's in a fancy neighborhood that's zoned for single families. They didn't want a cultural institution.

I was approached originally by the people who ran the house, who answer indirectly to the German government to be president because they thought I could deal with the neighbors. I didn't know if I could or not. I had never dealt with neighbors resisting a real estate development before. It turned out that CalArts was good preparation for trying to find compromises, reassure people and give enough guarantee that action was going to happen.

If it's a crisis today, it'll still be a crisis tomorrow. So, it doesn't have to be solved today.

We worked it out anyway. I became Founding Director, always understanding that after a few years, a young German would be hired to run it and I would become Chairman of the Advisory Committee. My friend said, “What are you doing? You spent your life in the arts, and now you are dealing with democracy. What do you know about democracy?” I said, “I don't know too much about democracy but I know one of the things that democracy, at least American democracy, is based on. It's not voting. It's what chance you have in this life.”

That became a guiding principle. I had also learned at CalArts that I didn't like scholarships. I love learning things. I have learned that at the Rockefeller Foundation, too. I threw myself into reading social history, political history and political economy. In a nice irony, I discovered that things that are our faculty were teaching twenty years before I was now reading were way ahead of me. I understand the world's social situation and the challenges to democracy. It has been wonderful.

I always thought when I was semi-retired, I would go back to college and start again. I thought I would do my literary education again with the idea that I know something about the world. It’s not just storytelling. I'm getting a college education again but in a different realm. I’m loving it and loving the sense that I don't know if we are making a big difference or not. Part of the principle behind the house was bringing American thinkers together with their German peers with the idea that if we are going to sustain democracy, it's going to be Europe and the United States working together and not even all of Europe any longer.

In some sense, Germany has become the strongest democracy in the world, as we have far questioning of many people our democracy. It feels like very powerful work as we try to bring those two worlds together and encourage fresh thinking about how do we renew or restore some faith. Democracy, while slow, is a problem-solving activity. You are better off trying to solve it together and turning all your authority over to an autocrat and trusting someone who says like Trump, “Only I can fix it,” and then doesn't fix anything as the autocrats rarely do. The temptation to believe that there was someone who had been fixed, everything is hard to resist when the world doesn't seem to be working on your behalf any longer. There are a lot of people in America for whom America does not seem to be working on their behalf.

I think about this and what you shared, and there's something about that. It is a combination of all the things that you have taken from all of your learnings and your journey as a whole. Something you said earlier, and the word that has come up a lot is the principles. That's so powerful when you lead by principles and you understand the principles that you stand by. It can change the game for you. It's been able to allow you to come back to them even when you don't know truly all the things that are happening.

Even in this job, when you were working with Thomas Mann, this is interesting because it has a lot to do with bringing people together in collective and seeing that, it's the diversity of thinking and this fresh perspective, fresh thinking is the way that you bring people together. You get them to converge around ideas. I often say the word like, “Divergence to convergence.” That's where that diversity that you have always been championing has been important. It's also about collaborating in that divergence.

One of our challenges as a country with this huge split right down the middle is we've got to find a way to talk to one another again and not see the other people as the enemy, which sometimes I feel with the QAnon people start in, they do feel like the enemy when people attack the Congress. They are also trying to make a country that they can believe in. We are doing a conference in 2021. Everything had to be virtual at the Thomas Mann House online.

For 2022, we are doing a big international symposium on trust and mistrust in government, asking what's the role of various sectors of society in bringing us back together again. What can we still share? It's a challenge if we can't even share the idea that vaccination is a good thing in the face of an epidemic, it's hard to find what we can share and think about stories around the campfire. One of the things you learn is that it's easier to find a story that's comforting to you than to find a story, which has some real truth in it.

I think that you hit the nail on the head when it comes down to it. There's an element of we often have our own internal stories but the idea is that how do you ensure that we have a story that's our common story that we can all believe in? There is an element of a collective story that has to come together and says, “What do we all believe as a people?”

We've got to believe that even if you admit some of the ugly stuff in our past, you can still be someone who believes deeply in this country. One of the great miracles of our country, given the way we have treated African-Americans from the beginning, they remained the great believers in democracy and the great defenders that it can work, even if it's not working. That's why Martin Luther King remains almost a saint. He kept insisting we are in this together.

That hope that keeps us going is so important. I could have this conversation for hours. Unfortunately, we have to come to a close. There's so much to cover. I have one last question I do want to ask and that is, what's 1 or 2 books that have had an impact on you and why?

I suppose that the books that have had the greatest impact on me turned out to be quite old books. George Eliot's nineteenth-century novel called Middlemarch. It's about a woman trying to understand how her life can mean something in the world. What influence can you have for the good? She makes a lot of mistakes in the process, in this hunger to contribute. That was an early formative book for me. I'm sorry, these are clichéd, great novels but Tolstoy's War and Peace, which I read every 5 or 6 years, in part for its comprehensiveness and the way the various parts of the world fit together and one thing influences another.

For the way, characters can deeply believe something one minute, and then the circumstances change. Suddenly, they believe something else fervently. The third book that's mattered most to me, I read it every five years or so, is Melville's Moby Dick. For me, I feel this hunger that there be some greater transcendental value somewhere that we can live by. You don't have to make it up for yourself. It is good and evil. There's a way to align yourself with that. That's what Moby Dick is all about. I'm not a wild person and it is such a wild book. All the parts of me that are repressed come out when I read that book.

First of all, what an amazing three books that you have mentioned. When I think about it, this is why I asked this question because it gives a sense of the depth that you dig into these books. They are classic. Two of the books, at least I know of. The other one, I don't know quite as much but now I'm intrigued. I'm going to go find out more.

You don't have to be very smart; what you need is to know what you believe in.

It made me think of some other books that come to mind. Have you ever read In the Heart of the Sea? It's basically the story of Melville's Moby Dick but told from a different perspective. I very much have enjoyed the stories you have shared. The depth of your insights has been profound. I'm so grateful for you coming to the show and sharing. Thank you.

It's a pleasure to talk to you. You've got a gift for this. You make it easy and fun.

I'm so thankful for that. That makes my day. Before we let you go, I want to give people a chance to find out where they can find out more about you. What's the best spot to find you?

The best place is www.StevenDLavine.com.

Obviously, we would be going out and grab your book, as well as your wife’s book.

Thank you. I would love that because some of the stuff we talked about is in the book, and some go further because I’ve got a whole book to do it in.

It’s such a pleasure. Thank you again. Thanks to readers for coming on the journey with us. As you can see, we scratched the surface. If you want to dig further, find out some more.

Thank you.

Important Links:

- www.StevenDLavine.com

- Thomas Mann House

- REDCAT

- Steven D. Lavine. Failure is What's It's All About: A Life Devoted to Leadership in the Arts

- I've Been Walking

- Middlemarch

- War and Peace

- Moby Dick

- In the Heart of the Sea

About Steven D. Lavine

Steven D. Lavine has been president of the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) since 1988. The CalArts community includes the Roy and Edna Disney/CalArts Theater (REDCAT), a center for innovative visual, performing and media arts, in downtown Los Angeles. Dr. Lavine, a graduate of Stanford University (B.A.), and Harvard University M.A. and Ph.D.), a leader in the cultural life of Los Angeles as well as the nation, was recognized with the “2005 Los Angeles Highlight Award” given by W.O.M.E.N. Inc. of Los Angeles.

Steven D. Lavine has been president of the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) since 1988. The CalArts community includes the Roy and Edna Disney/CalArts Theater (REDCAT), a center for innovative visual, performing and media arts, in downtown Los Angeles. Dr. Lavine, a graduate of Stanford University (B.A.), and Harvard University M.A. and Ph.D.), a leader in the cultural life of Los Angeles as well as the nation, was recognized with the “2005 Los Angeles Highlight Award” given by W.O.M.E.N. Inc. of Los Angeles.

Dr. Lavine currently serves on the board of the Idyllwild Arts Foundation, the Cotsen Family Foundation, and Villa Aurora Foundation for European-American Relations, as Co-Chair of the Arts Coalition for Academic Progress for the Los Angeles Unified School District. He has served on the board of directors of Endowments Inc., KCRW-FM National Public Radio, The Los Angeles Philharmonic Association, The Operating Company of the Music Center of Los Angeles, KCET-Public Broadcasting, Arts International, Inc., the American Council for the Arts, and the American Council on Education, and as a member of the Visiting Committee of The J. Paul Getty Museum. Dr. Lavine has also been co-director of The Arts and Government Program for The American Assembly at Columbia University and co-chair of the Mayor's Working Group of the Los Angeles Theatre Center. He participated on the Architectural Selection Juries for the new Los Angeles Cathedral and the Los Angeles Children's Museum. In 1991, he co-edited with Ivan Karp, Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display; in 1992, the Smithsonian Institution Press released their second co-edited volume, Museums and Communities: The Politics of Public Culture.

0 comments

Leave a comment

Please log in or register to post a comment