How Honesty Impacts Your Team With Ron Carucci

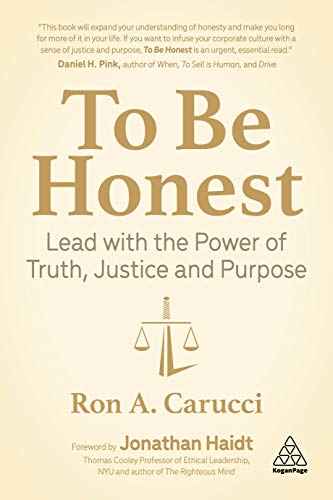

When it comes to doing business, honesty often becomes a blurry topic. But why is it important to highlight honesty, especially when managing your team or even your organization? Joining host Tony Martignetti is Ron Carucci, the Cofounder and Managing Partner at Navalent. Ron is also the author of the Amazon bestseller, Rising to Power, and, more recently, To Be Honest: Lead with the Power of Truth, Justice and Purpose. Today, he shares significant flashpoints in his life that pushed him to start his company to help CEOs and executives pursuing transformational change for their organizations, their leaders, and industries. Ron also discusses highlights from his latest book and defines honesty and its impact in the organizational context. Tune in to this insightful discussion on leadership to learn more!

---

Listen to the podcast here:

How Honesty Impacts Your Team With Ron Carucci

It is my honor to introduce my guest, Ron Carucci. He is the Cofounder and Managing Partner of Navalent, working with CEOs and executives pursuing transformational change for their organizations, their leaders and industries. He has several years track record helping executives tackle challenges of strategy, organization and leadership. From start-ups to Fortune 10s, non-profits to heads-of-states, turn-arounds to new markets and strategies. He has done it all.

He has helped organizations articulate strategies that lead to accelerated growth and designed organizations that could execute those strategies. He has worked in more than 25 countries on four continents. He's the author of nine books, including the Amazon number one, Rising to Power and To Be Honest: Lead with the Power of Truth, Justice and Purpose.

He is a popular contributor to the Harvard Business Review, where Navalent’s work in leadership was named one of 2016’s management ideas that mattered most. He is also a regular contributor to Forbes and a two-time TEDx speaker. His work has been featured in Fortune, CEO Magazine, Business Insider and MSNBC. He's everywhere. He and his wife live in Connecticut, where they are so happy to be back. Ron, I want to welcome you to the show.

It’s great to be with you. Thanks so much for having me.

I'm so thrilled to have you here because I've been following your work for many years and I just admire what you do and how you're doing it. One of the things that we do in the show is really show people who have shown up in the world so powerfully, but I want to unwind and see your journey to getting who you are.

Let’s dive in.

What we do in the show is we share people's stories through what's called flash points, points in your journey that have ignited your gifts into the world. As you're sharing, you can start wherever you'd like and we'll pause along the way and see what's showing up. We'll see what themes or things we want to dig in deeper. Take it away.

Telling great stories is interesting, but engaging people in the story is profound.

I began my career in the arts, a very different field than the field of organizational psychology that I'm in now. I studied in school in New York City at a great and prestigious school for the arts. I worked and most of my friends would be super jealous of the jobs that I was getting. I was learning that I bore easily and I'd be thinking, “I have to do the same thing eight times a week for how long?” After a while, I realized I wasn't sure I had chosen the right career. I chose the career defiantly. My parents had planned on me being a doctor.

I left New York City, went traveling and roaming the world and went on tour with a company that had contracts with the US Military and State Department in Europe, so I was living in Europe for three years. It was an interesting company that blended a lot of different mediums in arts with how they taught, trained and engaged with human beings. In one particular workshop, we were in the chapel at Dachau. It wasn’t lost on anybody that we were in this building, symbolizing love that was placed in a place symbolizing hate.

Back then, the term diversity and inclusion didn't exist, but that's what this workshop would have been called if it had been a term. It was something about managing differences and there were people from military, state government, civilians, East Germans and West Germans. The curtain had not fallen yet, but there were negotiations of conversations and there was a room full of different people.

In one point in the program, a young soldier stood up and he said, “I am just so tired of being trained to hate.” I remember being quite stunned by that, but my first thought was, “How did something we did out here make him think that?” and I wanted to know. He very vulnerably processed it as a group in the conversation, but I wanted to know more afterwards. You're in Munich, you go out for beer. That's what you do, so we went out and we were out late. I was fascinated. He wasn't much older than me. I was so stunned by his story and what it was he was thinking about in his own life.

That was the turning point for me, where I began to realize telling great stories is interesting, but engaging people in their story, that's profound. I would never get bored doing that. That’s what began my long arc of career change into organizational psychology. I came back to the United States and learned that there was a whole field, so I transitioned my career. That would probably be the earliest flashpoint for me. I spent my career inside the big companies for the first 5, 10 years.

As I've developed a passion for organizations and for human endeavor at scale, I learned that I didn't have great diplomacy skills and that you need those inside companies. I found myself collecting severance packages, which my kids love because it meant more time with me, but I realized that I don't think this is the way to do this work. I realized that when I would do the work from outside companies, so in between gigs, I’d consult.

The same exact behavior that got me into some trouble. Inside companies got me paid well and rewarded outside companies, so I thought if I'm going to live out my passion for organizations, it's going to have to be by not being part of one. I switched to consulting and I opened up my own practice, but after a year, I was in my mid-late 30s, I realized that I didn't know enough to do this forever. I know just enough to be a jack of all trades and master of none, but I knew that things I wanted to do, I wanted to influence the gatekeepers and the senior leaders.

The same exact behavior that got me into some trouble. Inside companies got me paid well and rewarded outside companies, so I thought if I'm going to live out my passion for organizations, it's going to have to be by not being part of one. I switched to consulting and I opened up my own practice, but after a year, I was in my mid-late 30s, I realized that I didn't know enough to do this forever. I know just enough to be a jack of all trades and master of none, but I knew that things I wanted to do, I wanted to influence the gatekeepers and the senior leaders.

It took a year, and a major flashpoint for me was the decision to sell my practice to a boutique consulting firm in New York City. It was the Rolls-Royce of consulting firms in my field. If you were a New York side person, this was the place you wanted to go. It was a prestigious firm and full of brilliant practitioners. It was a pretty intense process to get in and they only hired once a year, so that next year, I joined them.

I took my practice with me and spent eight amazing but difficult years there. Like every high-performing culture, there's always a couple of strings of cultural things that suck like being put in the Shawshank Redemption Camp if you do something wrong. It was a guru-centered firm, so the guru himself was a brilliant mentor, but also a little bit psychologically ill. After eight years there, I had everything I had hoped to learn, and then some. I had the incredible privilege of learning there, but then David sold the firm into a much giganto firm, and then that stopped being fun because that was all about feeding the dinosaur and not the craft. I loved the craft.

A couple of friends of mine and I said, “We can still go do this on our own. We can love this work. It had to be here.” We made the difficult but wonderful and very naively decision to go and do this work on our own. We never said, “Let's go start a firm.” We said, “Let's go do this on our own,” which is an important distinction because we weren't thinking about being entrepreneurs and starting a company. We were just saying, “We can go do this on our own. We should probably have a brand. We should have a website.”

It became this stumbling into our own thing, and Navalent was born. We realized that if we're going to do this at scale, we need more people. We have to hire people, that means we're going to have to manage them, and so it became this classic accidental entrepreneur stumbling our way through a firm. It's been a phenomenal run with a lot of fits and starts, ups and downs, puts and takes, but we have had years of making a difference for a lot of leaders in companies and it's a privilege work. Those are 3 or 4 hairpin turn flashpoints for you.

There's something about people wanting to go into consulting and thinking that it's easy. Put out a shingle and become a consultant, but there's always this dichotomy of going it alone as a consultant is not quite as easy. You have to build those skills and experiences still and get out there and be open to the pivoting in going into that direction.

It’s a feast or famine lifestyle. This was back at a time when the playing field wasn't so crowded. Coaching was just on the rise, now everybody and their mother is a coach. You go to Costco and get a coaching certification. The number of people that have hung out shingles who are, sorry to say, qualified to be giving any advice to anybody. Seasoned practitioners, that's who we're being compared to.

There’s a new generation of managers in place and CEOs that I worked with then are all retired. They don't know the difference. You can save it around 17, 20 years are doing this for 35 years. They're going to look at the person and says, “They're only $200 an hour, so why are you so much more money?” You could hire them and find out, and then you can call me in when they've ruined your company.

You bring up such a great point, too, which is to say that the part of the journey of becoming who you are and becoming the person who provides those insights is by going through and making all the mistakes and dealing with the toxic leaders that you've dealt with, and then through those mistakes that you've made, so that experience is not to be discounted. Also, knowing that because you've seen that, you charge what you charge because you've realized that the value you get from that experience is unmeasurable.

We don’t even charge by the hour or the time how we build our work but you’re not paying for an hour of my time, you're paying for the several years of experience. We need to learn how to solve the problem you’ve had in five minutes, that'll take you years to solve. Everybody's entitled to hire who they want to hire and I wouldn't begrudge any coach the ability to earn a living provided that they're qualified to be helpful.

If we don't keep ourselves fresh with dreams, with aspirations for something more, with a sense to keep evolving, that's when we get stuck.

I'm sure you've seen many of them. The people out there who somebody said, “You can give advice, you should be a coach,” so they go, “Okay.” It's like the person who auditions for The Voice whose mama told them they could sing, and they open their mouth and be like, “Mama lied to you.” Somebody is a mensch of a human being and they're not afraid to start to speak their mind, but that doesn't make you a coach.

A classic one is when an executive retires but doesn't want to retire full time and says, “I'll become a consultant.” There are certainly years of wisdom there that are worth something but it makes the playing field very cluttered for people who are trying to make important decisions about partners to help them with important opportunities or problems.

I want to dig into the humble years of your early entrepreneurial endeavor. Share a story about maybe an experience that you had early days with a company you walked into, knowing that the CEO or the senior leader are in need of some help and they were reluctant to embrace that help. Do you have an experience like that?

Sometimes CEOs or executives will call who know they're in trouble or know they need help and want it. They don't often conclude that they're part of the problem as much as they should, but we still are asking the right questions. Early in our days at Navalent, we were 1099-ing each other’s checks. It was a wild, wild west. We had clients that some of which whom came with us from our bigger firm. Mindy and I got called into a healthcare system in the Midwest that rent a bunch of rehabilitation facilities. We thought we were watching an episode of The Office.

The head of IT, a nice woman, but she would go, “Let’s be quick.” These were a strange set of people. We hear these horrible stories about the CEO who’s having an affair with the head of marketing, and the wife was doing the business someplace else. It was this like Peyton Place of nutso stuff. We're like, “How do we diagnose this? We can't put this data in front of anybody. We’re going to out people.” We weren't laughing, we wanted to cry because his patients were relying on people's help here and needing care, and this bunch of yay who's running the place.

It wasn't that we hadn't dealt with difficult things in our career before like that, but we're it. There's no big firm or big brand behind for you to hide behind, this is you. It was touch and go there for a while. We managed to get our way through piece by piece. We put out the best duct tape, the best chewing gum and band-aids on it that we could to try and get it to function well, but it was not an easy go of it.

There was only a few of us so trying to figure out who we were, what was our brand was and arguing over stupid things like website colors and silly things. Eventually, it went to a very painful place where 1 of our 3 founding members, we needed to part company with them. That was an agonizing, heart-rending choice because we all started this very naively, without the real sense of our shared aspirations, other than we love the work and we liked working with each other.

The real problem was that we ignored the signs. We saw the signs. We ignored them early on that it was going to be a fissure. We waited too long until there was a disaster and then we had to act. It was painful. That cost us five years of our own growth experience to get through and recover from. All attorneys will tell you when you're creating an LLC to be vigorous, sharp, thoughtful and document everything. They’ve seen many things fall apart without that and we're like, “We love each other. We’re going to be fine.”

One of our genuine litmus tests as a community in Navalent is that if when this is all done, we're not sitting on the porch of the same old person’s home, rocking in our chairs, talking about dancing in each other’s kids’ weddings, this didn't work. That was our yardstick, and so we believed in that vision but we were naive about what could go wrong and what did go wrong. It took an agonizing and painful year of embroiled battles to end that relationship. Those moments are costly for any entrepreneur. We had given better advice, we just didn't follow it.

What's beautiful about this is that what you're sharing is the very thing you've learned, and you're able to help others through that journey and hopefully help them to see these challenges before they hit them.

The scars are still there and it's still sad. That was years ago. We're more thoughtful now and much more scrutinizing about how we invite people into the community. There have been so many more areas of Navalenters. We have quite a nice, robust group of Navalent alumni out there, too. We have one partner with us for 12, 13 years when some people can stay 3, 4 or five years then move on in their career. That's always painful because we're such a small community. I'm going to be here forever. I have a tattoo of our company logo on my leg.

This is the last company I'm working for. You hope people will stay, but you also recognize people have aspirations, dreams and careers they want to go on. When you have somebody with you for five years and you've trained them and they're great, and they become part of your world that when they move on, it's a painful thing, but it's a part of reality and part of the limitations of being a small firm. I can give people a lot of things that a big company can't get them, but a big company can’t give them the things that I can.

At some point, you have to know when to call it, when to say it's time to move on, when it's time to separate relationships with other people, or to know when it's time for you to move on from being in a certain role that you own. I know that you work with a lot of people who are maybe in that role where it's no longer their time to be the leader.

Many of them don't want to face that, especially if they are later in their careers, you can watch somebody's fear of obsolescence just paralyzing them and they can't name it. They can't be honest about their need to be indispensable. If nothing else in their head, but sometimes even in real life, they made themselves indispensable by hoarding knowledge and becoming a go-to person, and the notion of having an identity beyond that is terrifying for them because they don't see one.

When I work with retirement executives, I often hear the notion of, “The only thing I've ever failed at in life is retirement,” because they don't have a life beyond that. They don't have any sense of identity beyond a title of the role or the wealth they've accumulated. If we don't keep ourselves fresh with dreams, with aspirations for something more, with a sense of our agency to keep evolving, that's when you get stuck.

What's sad, and I'm sure you read these stats a lot, our peer group is suffering. Men in their 40s and 50s, suicide rates are all-time highs, depression and anxiety, it's terrifying. They went on cruise control at 33, on a career conveyor belt, got married, had kids, had a mortgage, rubbed their eyes. Eighteen years later, their kids graduated from high school and they feel like, “What was it all for?” It's not too late to answer that question, but it's a much harder climb to start answering that question at that point in your life, and some guys opt out, which is tragic.

I'm glad you mentioned that, especially given the times that we're in where people are feeling more disconnected. There's an element of feeling disconnected from the people in the office and working remotely. That even amplifies that emotional feeling that those men are having. I want to pivot a little bit into the topic of your book about honesty. What is it that is the key concept that you want to share people around what it is to be honest?

More than anything else, it is that we can all be better at it. This is an ass-kicking book. Fifteen years of research and 3,200 interviews with leaders. We’re all tired of the stories and the lame explanations for the stories of Theranos, Wells Fargo and Volkswagen. People are still talking about Enron. They leave incredibly deep scars in institutional trust.

I was tired of, “It was a couple of bad apples. It was just the culture,” those exclamations were so unsatisfying. I thought, “What would turn otherwise good-hearted people into cheats and liars? How does that happen?” Nobody has to look around that far. Look at any headline to see why trust in leaders and institutions has fallen to all-time lows. What does it mean to be trustworthy? What does it mean to earn and keep the trust of people who are important in our life, whether in our organizations or our personal life?

I wanted to know how it is people go about losing that trust without even realizing they're doing it. I thought, if we could predict the conditions under which people will make the wrong or the right choice, could we proliferate the good ones and prevent the bad ones? We used some sophisticated IBM Watson statistical modeling software to analyze these data. My goal wasn't set out to write a book. My goal was to just learn, but the data was so compelling that in fact, we can correlate four provable conditions.

We learned in the research that honesty is not a character trait. Honesty is a muscle, it's a capability. It’s something you have to be good at, and if you want to be good at it, you have to work at it. Nobody goes to the gym on their first day and bench presses 300 pounds. You have to work at that. The same is true for honesty is a muscle, you have to work at it, especially in hard moments of honesty, if you're not prepared for those.

Honesty is not a character trait. It is a muscle, a capability. It’s something you have to be good at, and if you want to be good at it, you have to work at it.

Honesty is no longer enough to be labeled that you're not a liar to be labeled honest, that might get you labeled as a nice person. We've found that honesty is quoted in three dimensions, truth, justice, and purpose, meaning you have to say the right thing, do the right and fair thing and do the right and fair thing for the right reason.

It's all three of those things that gets you labeled as honest, and we found four conditions in organizations and in leadership that will predict or shape whether or not you will be honest in those three areas or whether you won't, and it was exciting. I wanted to write a book of heroes. I wanted to write about a book of the people we all would be thrilled to follow, or would die to emulate in some small way. I wanted to write about the stories and curate the stories of people I'm inspired by, who embody honesty in ways we should all aspire to, so that's what I did.

I'm compelled to ask this question about the people who say, “Honesty has some gray areas to it.” Have you had people push back and say, “Aren't there some gray areas if I'm honest all the time, then it might hurt people?”

That’s an issue of cheap excuses. Honestly, should never have to hurt people. Should I tell my partner that the dress makes her look fat? That's not a question of honesty, it’s a question of stupidity. It has to do with whether or not you're honest. Your decision to withhold feedback from somebody who needs to hear it under the guise of, “I don't want to hurt their feelings,” is just your cowardice. To withhold information from someone that could help them be better is not only not kind, it's cruel.

Are there areas that can be subjective? Yes, that's what judgment is for. What people are not doing is scrutinizing their judgment. It’s interrogating the, “On what criteria are you?” You're saying, “This is for the good of the enterprise. It's about discretion. This is proprietary secrets.” Here's the litmus test, if your decision lined up with the cover of the New York Times, would you be okay with it? Would you tell your mother? If you struggled to answer those questions, then there's no gray area, but if you can say, “Yes. I'd be fine. I could defend the decision in the New York Times cover story and I’d tell my mom.”

There are two things that come to mind that as you described this. One, it's a muscle that gets built. It's not like you just arrive and know what to do all the time. To be honest, you have to continue to think about, “How do I build my ability in knowing how to make the right choices at the right time, and to be honest with people in the right context?” Secondly, all comes from having a strong understanding of what you value as a foundation for the people who work for you, for them to see that they've chosen the right leader who has the right values.

What are the criteria? The four findings. It was indeed who you say you are. All of our organizations make promises in their value statements, in their brand statements, in their purpose statements and in their missions. All leaders make promises through their encoded values. If you've not told people what you value, they're going to figure it out anyway. They may figure out that you value something you don't think you value. You may figure out that you value efficiency over compassion, or that you value your own career over theirs despite what you say.

Here's the harsh news, when your actions and words don't match as an organization or as a leader, you are three times more likely to have people around you be dishonest, because what you've done is you've institutionalized duplicity. You've said, “Around here, it's okay to say one thing and do another.” If people take your vision statement, your value statement or your purpose statement, and with it, roll their eyes. That's for just external consumption, but that's not how things work around here. You're in trouble. You’ve inserted a three X risk factor for dishonesty.

I had to give feedback to a client that his team, he had lost their trust. He got very defensive and he said, “What do you mean? I've never lied to them. I'm always straightforward with them. I include them in decisions and they know exactly where I stand. How could they not trust me?” I said, “Apparently in meetings, when people have things to say, if they go on a little bit too long or aren't quite as crisp as you want them to be, you can be a little sarcastic or you cut them off when you get tired of listening to them.”

He said, “Everybody has a bad day.” I said, “Apparently, you have a lot of them. What you have told people is you are not safe for them to speak up around, so they get anxious before they speak. They worry about when your little daggers would come out and poke them. They're so worried about getting their point out that they babble, because you make them anxious and then you cut them off anyway, and you make their worst nightmare come true. By virtue of the fact that you are not safe to speak around, you are not trusting.”

This is a good guy. He's not a jerk but would have never connected trustworthiness to how he creates the tone of a conversation in a room, but he had always been the first to tout teamwork. “We're all for the team. Teamwork's important and we have to collaborate.” I said, “You have belied the very value you say you espouse with behaviors that punish people for not being like you and how they articulate themselves.” The point is we all have blind spots where our actions and words don't match. If you cannot reduce your say-do gap, people will make assumptions about you that maybe you don't want them to make.

You brought to life the work that you do. This is why it's important that we do need someone to reflect on us. Are we doing the things we want to do to elicit the response we want from the people around us? Oftentimes, we miss it. It's not because of ill-intent, it’s that we don't see the things we don't see. The blind spots. That was a great way to bring it. One thing that came to mind was this ability that your true values speak louder than you do. You can't say you value integrity and then you're over there stealing office supplies.

All the factors we've done are things that are hiding in plain sight in your organizations. They're all conditions we all assume are daily or regular organizational nuisances that have risk factors in them associated with whether or not people will be honest with you.

I want to shift gears slightly and get back to you, and understanding what you have learned about yourself in the journey of getting to this place where you are now. Maybe 1 or 2 things that you'd like to reflect on your journey.

When I met Dorie, it was a dark place. I was in a discouraged and uncertain place about my voice in the world and how I wanted to use it, what I was doing wrong and not understanding. I recognized that the cluttering landscape was just cluttering by the day with a lot of stuff and I didn't know how to navigate it, and I didn't want to. My network was retiring. If I was going to continue to feed my firm, I needed to rebuild my network.

I'm a sucky networker and I don't like it, but I could create content. I knew how to do that, so that was the way I chose to try and attract a different network, or brought network. I didn't know how to do that, I thought I did, but it turns out I didn't. When I started working with Dorie, I stalked her in LinkedIn for a while, and then she caught me stalking her. She popped up in a message with, “Can I help?” She caught me, so I said, “I might have a client for you.” I didn't tell her it was me.

We got on a Zoom call and I told her it was me, but I could hear my judgments in my mind evaluating her as a consultant like, I'm going to use my standards of what I do to see if she's a good consultant and what kinds of questions does she ask, how well does she poke, how does she challenge and how does she express her advice. She was brilliant. She wanted to say, “Do you want to try and work at it for six months?” I said, “Can we do the diagnosis first? Let's make sure we both agree that I’m helpable before we commit.” She said yes, so she did her diagnosis and came back.

It was a Sunday morning when I got that report and I’m like, “This is what it's like to be on the other side of me.” My hands were sweaty, I could feel my mouth getting watery and about to be this however many pages her report was. I cried, laughed, sighed and you get all the reactions to data that's accurate and somewhat encouraging, but also painful. Mostly had to do with the fact that I was at a point in my career where if it had been several years early, I'd have been great and excited.

There are a few years ahead of me and they're right behind me. I'm optimizing for a very different window of time than her feedback would have allowed. One of the things we do in our diagnostic work as a firm, which is one of the most powerful things we do, is what we call a Navalent Point of View. When we report our data back, it's just the story. This is the story you are telling yourselves about you. We've organized it for you in a way you haven't seen it, but now we'll tell you what we think about your story.

To withhold information from someone that could help them be better is not only unkind; it's cruel.

Dorie reported back the data with her insights. I wanted to know what she thought. I wanted to know the key questions for me that the data didn't report out, so I said, “This is great Dorie. I’m looking forward to our debrief. When you come to our debrief, I'd love for you to come prepared to answer the following questions. I'd love your thoughts on these.” I was thinking that in the next day or two, she’d come with them, but 2 or 3 hours later, I got this eight-page email answering all the questions.

My head wanted to detonate. It was so amazing. It was everything I needed to hear. I'm like, “I'm going to work with this woman.” She's become one of my dearest friends in the world. Every now and then, I put her back on retainer to help. I probably sent her 1/3 of the rest of the community. I love her to death and I'm very privileged to be a story in her book, The Long Game, but it's painful. You have to be ready for how painful it is everyday.

One scroll through LinkedIn is all you need to want to pour two glasses of wine, spend too much money on Amazon, or do something addictive to numb the pain. It is a psychological assault and that's part of the deal. Writing or launching a book is an existential crisis by definition. It is nothing more than a mirror of your inner mental health. Whatever your predisposition and triggers are, they're going to come roaring out of you all the time. I was not ready for any of that. That's not what I thought I was signing up for.

As a psychologist, I should have figured, “That's what you're signing up for. That's exactly what it is.” Years in hindsight, I get it, but I would tell anybody who's thinking about completing that journey of competing on ideas of getting people to hire you for the things you can solve for, or the support or help you can offer. You have to back up those ideas for proof or some codification that says you're not making this stuff up, you better fasten your seat belts and hold on because that's going to be the ride.

Being challenged by a community or by people who seemingly are knocking it out of the park, doing great things in the world, is that feeling you have of like, “What am I doing with these people?” That uncomfortableness is exactly what you sometimes need to push you to that next evolution.

What’s great is that it’s not this community. This is a community of cheerleaders and people who will bear your burdens and who all get it. We all want to do the comparison. It's useless. It's a waste of time. This is a community of 600 people strong who you can go to for help at any minute. A bunch of people are going to show up and care for you but they're not going to put up with the crap. These are very special people.

The message that I've heard from so many people who have come on the show is this ability to say, when you put yourself in a community with people who are going to raise you up, it makes a big difference. You have to find your tribe and spend time with them and find ways to ensure that you’re connecting with them so that you can become the person you're meant to become. As we're coming to the close of our time together, I wanted to ask one last question. What are 1 or 2 books that have had an impact on you and why?

One book is a book that I try to read at least once every year or two. David Whyte's Crossing the Unknown Sea: Work as a Pilgrimage of Identity. It is about our relationship to our work and its relationship to us, and what form of identity it takes us. Beautiful book. It should be required reading for the planet. Anything that Manfred Kets de Vries wrote. He's one of my superheroes in our field. The Leader on the Couch would probably be my favorite book of his because he does such a beautiful job of bridging the clinic into the role of coaching. Mindful Leadership Coaching, it's a great book as well.

Given the horrible political mess we found ourselves in as a nation, Michael Sandel’s book, The Tyranny of Merit was a beautiful book. Understanding how we have left some people behind in our nation, why we've done it and how to heal that bridge. I got to interview him for my book. He’s just a wonderful man. Lastly, the last couple of years of my life, I've gotten very involved in racial justice as a personal passion for me, so Ibrahim Kendi’s book How To Be An Antiracist is a brilliant blueprint for all of us to understand the scourge of racism and its presence in the world and how we don't even realize it's there.

Thank you so much for sharing that. I have to thank you for everything you shared because every time I spend time with you, I feel like I'm learning so much that I'm taking away and internalizing and integrating into my own learning. I appreciate that. Thank you for coming to the show.

Thanks for having me. All the best to you and thanks for your good work in the world.

Before I let you go, I want to make sure people know where to find you and they know that your book is available on Amazon and they should grab a copy because it's brilliant.

Thank you. Come hang out with us, our website is Navalent.com. We got a treasure trove of videos and white papers and a bunch of free eBooks, so if you're looking to level up as a leader for your team or your department, lots of resources there for you to come to find. If you want to know more about the book, we did a TV series called Moments of Truth, so if you want to see the behind-the-scenes conversations I did with the heroes of the book, come to ToBeHonest.net. You can binge-watch all fifteen episodes. Either there, on YouTube, or if you have Roku. We're on Roku.

I've got some great co-hosts. Khalil Smith from the NeuroLeadership Institute and Jared Chappell, a partner in my firm, did segments on everyday justice and finding your voice. You get to meet all my heroes and some of their heroes, too. Every 30-minute episode, we'll just chuck full of weird stuff, and if you want to know whether or not you're getting the full skinny from your team, we have an assessment called How Honest is My Team. You can come to ToBeHonest.net/Assessment. Pour a glass of wine first, take the test, and see just whether or not you're getting the full scoop from those you lead. Please, follow me on LinkedIn or Twitter, or both. Please, do stay in touch.

Thank you again. Thank you to the audience for coming on the journey.

Be well. Take care.

Important Links:

- Navalent

- Rising to Power

- To Be Honest: Lead with the Power of Truth, Justice and Purpose

- The Long Game

- Crossing the Unknown Sea: Work as a Pilgrimage of Identity

- The Leader on the Couch

- Mindful Leadership Coaching

- The Tyranny of Merit

- How To Be An Antiracist

- ToBeHonest.net

- ToBeHonest.net/Assessment

- LinkedIn - Ron Carucci

- Twitter - Ron Carucci

About Ron Carucci

When an executive faces the challenge of a spearheading a daunting transformation of any kind, I'm the guy they call to make sure it goes well. I am co-founder and managing partner at Navalent, working with CEOs and executives pursuing transformational change for their organizations, leaders, and industries. I have a thirty-five year track record helping some of the world’s most influential executives tackle challenges of strategy, organization and leadership. From start-ups to Fortune 10’s, turn-arounds to new markets and strategies, overhauling leadership and culture to re-designing for growth, I have worked in more than 25 countries on 4 continents. In addition to being a regular contributor to HBR and Forbes, my work has been featured in Fortune, CEO Magazine, BusinessInsider, MSNBC, Inc, Business Week, Smart Business, and thought leaders.

When an executive faces the challenge of a spearheading a daunting transformation of any kind, I'm the guy they call to make sure it goes well. I am co-founder and managing partner at Navalent, working with CEOs and executives pursuing transformational change for their organizations, leaders, and industries. I have a thirty-five year track record helping some of the world’s most influential executives tackle challenges of strategy, organization and leadership. From start-ups to Fortune 10’s, turn-arounds to new markets and strategies, overhauling leadership and culture to re-designing for growth, I have worked in more than 25 countries on 4 continents. In addition to being a regular contributor to HBR and Forbes, my work has been featured in Fortune, CEO Magazine, BusinessInsider, MSNBC, Inc, Business Week, Smart Business, and thought leaders.

I'm the bestselling author of 8 books. I co-led a ten year longitudinal study on executive transition to find out why more than 50% of leaders fail within their first 18 months of appointment, and uncovering the four differentiating capabilities that set successful leaders apart. Those findings are highlighted in my Amazon #1 book Rising To Power, co-authored with Eric Hansen. These findings were selected by HBR as one of 2016’s “Ideas that mattered most."

I am a former faculty member at Fordham University Graduate School as an associate professor of organizational behavior. I have also served as an adjunct at the Center for Creative Leadership. My clients have included Abbvie, Starbucks, Microsoft, Coronal Energy, CitiBank, Corning, Inc., Lamb Weston, The Hershey Company, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Amgen, Deutsche Bank, Gates Corporation, MMC, Edward Jones Investments, ConAgra Foods, GSK, TriHealth, OhioHealth, Del Monte Foods, Midnight Oil Creative, McDonald’s Corporation, Sojourners, The Atlantic Philanthropies, Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, Cadbury, Miller Brewing, the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office, Price Waterhouse Coopers, Johnson & Johnson, ADP, and the CIA.

Love the show? Subscribe, rate, review, and share! https://www.inspiredpurposecoach.com/virtualcampfire

0 comments

Leave a comment

Please log in or register to post a comment